On Easter Sunday, April 5, Rolling Stone magazine retracted what is possibly the most controversial story in the magazine’s 48-year history, “A Rape on Campus,” written by freelance writer Sabrina Rubin Erdely.

But some things can’t be retracted.

That’s what I thought as I read “Rolling Stone and UVA: The Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism Report: An anatomy of a journalistic failure,” by Sheila Coronel, Steve Coll and Derek Kravitz. It is as exhaustive as it is enraging.

The 12,866 word report is the result of CSJ’s months’-long investigation into the December 2014 Rolling Stone magazine story. Erdely’s article detailed a grisly, brutal fraternity gang rape by seven men of a University of Virginia junior who the magazine called “Jackie.”

“A Rape on Campus” was an indictment of every aspect of the rape culture that has become pandemic on college campuses in the U.S. First, the article described the rapists who Jackie asserted had planned and plotted the gang rape, making them not “just” rapists, but violent criminal co-conspirators. Then there were Jackie’s three close friends–two young men and a young woman–who the article quoted as being more concerned with being able to attend more frat parties than with getting their friend to a doctor or reporting the gang rape.

An unconcerned and uncaring UVA administration added to the horror. And of course, at the center of the story was the Greek system that promotes rape in fraternities and in particular Phi Kappa Psi, the fraternity where Jackie asserted the gang rape had been coldly and demonically planned and brutally and violently executed.

Released April 5, the CSJ report and its stunning details forced Rolling Stone’s managing editor Will Dana to subsequently retract “A Rape on Campus.”

Dana had previously issued a brief apology for the article and had enlisted the unpaid and unaffiliated CSJ to investigate after other reporters at various news outlets including the Washington Post and Jezebel discovered numerous discrepancies in Erdely’s story.

But even though the article had been included in the Columbia Journalism Review’s “The Worst Journalism of 2014,” where it was awarded “this year’s media-fail sweepstakes” and had been named as the “Error of the Year” in journalism by The Poynter Institute, the article had still not been retracted until the CSJ report came in on the night of April 5.

Now it has.

Dana wrote in Rolling Stone online, “We are officially retracting ‘A Rape on Campus’…We would like to apologize to our readers and to all of those who were damaged by our story and the ensuing fallout, including members of the Phi Kappa Psi fraternity and UVA administrators and students. Sexual assault is a serious problem on college campuses, and it is important that rape victims feel comfortable stepping forward. It saddens us to think that their willingness to do so might be diminished by our failings. “

Erdely issued her own apology in which she said in part that reading the CSJ report was a “brutal and humbling experience.”

Not gang-rape brutal, but her journalistic-integrity-called-into-question brutal.

Erdely continued, “I want to offer my deepest apologies: to Rolling Stone’s readers, to my Rolling Stone editors and colleagues, to the UVA community and to any victims of sexual assault who may feel fearful as a result of my article.”

No mention of the fraternity. No mention of Jackie. And no mention of reportedly many other young women at UVA who came to Erdely with credible, verifiable stories but whose stories were apparently not salacious or sensational enough for either Erdely or Rolling Stone.

Both the New York Times and the Washington Post wrote detailed articles about the CSJ report and the Rolling Stone retraction on April 5. On April 6, Phi Kappa Psi, the UVA fraternity at the center of the article and Jackie’s allegations, announced it was considering a lawsuit against Rolling Stone over the “A Rape on Campus” article.

In a statement to the media, PKP said, “After 130 days of living under a cloud of suspicion as a result of reckless reporting by Rolling Stone magazine, today the Virginia Alpha Chapter of Phi Kappa Psi announced plans to pursue all available legal action against the magazine.”

Rolling Stone has declined comment on the fraternity’s statement.

The excuse Erdely has repeatedly given for her failure to interview anyone related to the story Jackie gave her is that she did not want to “re-traumatize” a rape victim. That’s an understandable statement–to a degree. But reporters don’t get to pick and choose what they report.

We don’t get to tell a story of a brutal rape by seven college fraternity brothers and not get all sides of the story. Reporting is like “Roshamon”–there is always more than one side to a story or there would be no story. Investigative journalism is–or is supposed to be–a piecing together of a puzzle which can only be done if one searches for all the pieces.

Erdely had one piece: the story from Jackie. That story was a horrifying, vividly detailed story in which she told Erdely:

“My eyes were adjusting to the dark. And I said his name and turned around. … I heard voices and I started to scream and someone pummeled into me and told me to shut up. And that’s when I tripped and fell against the coffee table and it smashed underneath me and this other boy, was throwing his weight on top of me. Then one of them grabbed my shoulders. … One of them put his hand over my mouth and I bit him – and he straight-up punched me in the face. … One of them said, ‘Grab its motherfucking leg.’ As soon as they said it, I knew they were going to rape me.”

Jackie told Erdely that her gang rape was planned and that it was part of the frat’s initiation rite.

We can’t know for sure why Erdely refused to interview any of the people Jackie told her about. Not the seven students who Jackie alleged had gang raped her. Not Jackie’s friends to whom she went for help, but who she told Erdely said they wouldn’t get invited to parties for the next few years if they contacted the UVA authorities or the police.

At no point did Erdely seem concerned by either her own failure to fill in the gaps in the story nor by details that were just difficult to believe–like the fact that Jackie said she was punched directly in the face by an athletic male college student and there was no mark on her–no black eye, no broken nose, teeth, cheek. No mark at all. Erdely isn’t new to journalism. She’s been a reporter for two decades.

So what happened?

The CSJ report lays out a series of failures to secure the story. No editor asked Erdely to fill in the gaps. Dana did not say the magazine was holding the story until the dots were all connected. Rather, what propelled the story forward was a deadline–for the December issue to hit stands in November.

That’s not how news stories get done.

I’m outraged by the Rolling Stone story. I’m outraged as an investigative reporter. I’m outraged as a feminist who has been writing here and in other publications about the epidemic of rape on both college campuses and in the larger culture. And I am outraged as a victim of rape.

I never believed Jackie’s story. I said this at the time “A Rape on Campus” was published and I am saying it again now. And had I been the reporter on this story, it never would have seen print because I would have interviewed everyone involved.

I would have started with Jackie.

After “A Rape on Campus” was first published, the story became one of us v. them. The “us” was rape survivors like myself and victim’s advocates. Every feminist I knew was supporting Jackie. A Twitter hashtag went up immediately. “Them” was anyone who didn’t believe Jackie.

Someone should have interviewed Jackie. And by interviewed, I mean asked the difficult questions. Like how did she manage to walk away from a gang rape perpetrated by seven young men, all of whom were athletes when she’d been raped and sodomized on a bed of broken glass? How did she not have any marks on her–not even beard burn or a split lip after being forced to perform so many different sex acts after being punched in the face?

These are difficult questions to ask, but they must be asked. They must be asked because more than one young woman’s veracity depends on it. Every subsequent rape victim in America will now be accused of “pulling a Jackie” from now on–it’s already happening online.

Throughout the timeline of this story which began with the alleged rape in 2012, no one has really asked Jackie what happened. Including, most importantly, Erdely.

According to the CSJ report, “if Jackie was attacked and, if so, by whom, cannot be established definitively from the evidence available.”

Police in Charlottesville, Virginia announced in March that they could find no evidence that a rape occurred. In deference to Jackie they added that she might have been sexually assaulted under different circumstances. But according to police, nothing Jackie said in the Erdely article was true.

Jackie did not cooperate with either the police investigation or the investigation by CSJ. According to CSJ, Jackie’s attorney told the CSJ crew that it was “in her best interest to remain silent at this time.”

No doubt. Especially considering that Jann Wenner, Rolling Stone’s editor-in-chief was quoted in the New York Times on April 6 blaming Jackie for the entirety of the scandal.

“The problems with the article started with its source, Mr. Wenner said. He described her as ‘a really expert fabulist storyteller’ who managed to manipulate the magazine’s journalism process. When asked to clarify, he said that he was not trying to blame Jackie, ‘but obviously there is something here that is untruthful, and something sits at her doorstep.’”

Not exactly.

I don’t know what happened to Jackie. I only know what didn’t happen to her. I do know how journalism works, though, and it doesn’t work like this. Reporters check sources. Editors check reporters. Fact-checkers check everyone.

None of that happened here and the damage that’s been done is actually incalculable.

Everyone has blamed Jackie for the Rolling Stone story. But is she to blame? If you tell a lie (and “fabulist” is another word for “liar”) and someone reports it as fact without checking its veracity, is only the liar at fault?

CSJ seems to think not.

I certainly think not.

There are many victims in this story, yet there is no punishment. Wenner and Dana both pretty much shrugged at the CSJ report. No one will be fired. Not Dana, not Sean Woods, Erdely’s immediate editor. Erdely herself–a freelancer, no less–will reportedly continue to write for Rolling Stone, which is perhaps the most astonishing thing as who will ever trust another word she writes?

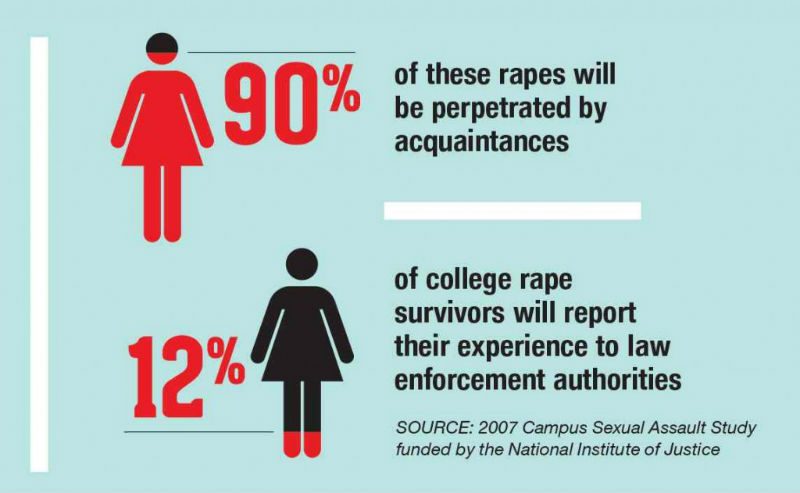

Rape culture is real. There’s a pandemic of rape on college campuses like UVA as has been detailed in the new documentary “The Hunting Ground.”Rapes happen at fraternity houses like Phi Kappa Psi all the time as Caitlin Flanagan wrote in her expose of fraternities in The Atlantic magazine, “The Dark Power of Fraternities: A year-long investigation of Greek houses.”

Disbelieving rape victims is real, also, although less than five percent of rape allegations are false reports. Yet when I reported my own recent rape in which I was badly beaten, bitten and choked, the very first thing the Special Victims Unit detective said to me was that if I were lying, I would be prosecuted. According to the detective who later, after he photographed my injuries, told me he had two daughters, women accuse their boyfriends of rape all the time.

The atmosphere into which I, as a middle-aged lesbian who had been raped by a serial rapist in broad daylight, dragged off the street in front of my own house, had to be told that if I were lying I would be prosecuted is the same atmosphere into which Erdely and Rolling Stone published their “fabulist” story.

On Easter night, post-family, I went on Twitter to catch up on the day’s news. The Rolling Stone debacle had drowned out the Iran deal and anything else. And imbedded in all the deconstruction by reporters and journalists I follow and connect with on Twitter was what I knew would happen when I first read “A Rape on Campus”: straight men saying that women always lie about rape and Jackie just proves it.

But no one is considering this: Straight men, who represent nearly 90 percent of all rapists, have an investment in women being caught out as liars about rape. And there were no women involved in this story (nor in most stories at Rolling Stone, which is known as a guy’s magazine) except Erdely and Jackie–both of whom Wenner blames for the trajectory of the story’s failures while not holding any of the male editors responsible for following through on their role in putting this story on the newsstands.

After “A Rape on Campus” was published and the story began to fall apart almost immediately, myriad excuses were made for Jackie’s “fabulism,” among them that rape victims are so traumatized they don’t remember details. (Everything Jackie reported, from the names of the alleged rapists to the description of the frat house were untrue.) And perhaps some don’t. I’m sure some women and girls just want to block it all out. Yet every rape victim I have ever interviewed and every woman I know personally who has been raped remembers everything that happened to her.

I remember every detail of when I was raped at 17 on my college campus by two men who offered me a ride home. I remember every detail of the recent rape I endured. I wish I didn’t. I would like to forget. I can’t. Rape changes your life. And perhaps Jackie was indeed raped and her rape so changed her life that she had to invent a bigger, more vivid, more terrible story to account for how much it had changed her life.

I doubt we will ever know.

What we do know is that in the world of online traffic, headlines draw readers. Clickbait headlines draw more readers. Editors want clickbait. I hear it all the time from editors. “Sorry, that story idea won’t get enough traffic.”

What we also know is that when rape is pandemic, one more campus rape is the same as another campus rape and one rape–unless it is our own or that of someone close to us–is no big deal. Erdely reportedly dismissed such stories when they came to her. They weren’t big enough. But a gang rape on a bed of broken glass by seven frat brothers with objects?

Now that was a story.