In this time of Trump, MLK Day has more meaning than ever.

“Why are we having all these people from shithole countries coming here?”

The query was the latest in a decades-long list of racist comments from Donald Trump. But unlike many of his previous racist jabs at Mexicans, a Latino federal judge, Muslims, black athletes and a black Congresswoman as well as his six years of attacks claiming former President Barack Obama wasn’t an American citizen, this one finally seemed a bridge too far—and has set loose an international firestorm.

Trump—President of the United States Trump—was referencing Haiti, El Salvador and the entire continent of Africa while in a meeting with members of the Senate to discuss immigration reform.

Trump queried why the U.S. wasn’t getting more immigrants from Norway, a tiny, majority-white Scandinavian nation that is also one of the wealthiest in Europe due to being the world’s fifth-largest oil exporter. The population of Norway is only 5.2 million, but unlike the U.S., expanded its population by 1.5 percent in 2017, with immigrants representing 75 percent of that growth.

Source: The Atlantic

Source: The Atlantic

Adding to his offensive language, Trump also said, “Why do we need more Haitians? Take them out.”

It was a far cry from 2016, when while campaigning in Florida, home to more than 40 percent of Americans Haitian immigrant population, Trump had claimed he was a friend to the Haitian people and would help the Haitian community as president.

Twitter and Facebook blew up with responses. Cable news pundits were aghast. FCC norms were tossed as anchor after host after pundit after guest added “shithole” to their collective lexicon.

In a presidency highlighted by its vulgarity, Trump seemed to have reached yet another apex.

Everyone is now saying #shithole on TV, f*ck the censors.

That’s where Trump has brought us as a nation.

Screw civility.

Dragged us right into the shithole with him.— Victoria Brownworth (@VABVOX) January 12, 2018

The outcry over Trump’s words, which he didn’t deny the day they were said but which he attempted to walk back in one of his early morning tweets the next day, was resounding. World leaders took to Twitter to condemn his statements, as did Democrats. The head of the African Union demanded an apology. Throughout Africa. U.S. ambassadors were asked to account for Trump’s words. And international outrage continued to simmer.

Only a handful of Republicans pushed back at the president. The first to do so was Rep. Mia Love (R-UT). Love is the first black Republican woman elected to Congress and the first Haitian American.

Here is my statement on the President’s comments today: pic.twitter.com/EdtsFjc2zL

— Rep. Mia Love (@RepMiaLove) January 11, 2018

The muted response of Republicans was itself an outrage, particularly as the Martin Luther King Day holiday loomed. How could a single member of Congress remain silent at this of all times? Some had trouble characterizing Trump’s words as racist, using words like “unhelpful” and “unfortunate.” CNN’s Anderson Cooper was not among them.

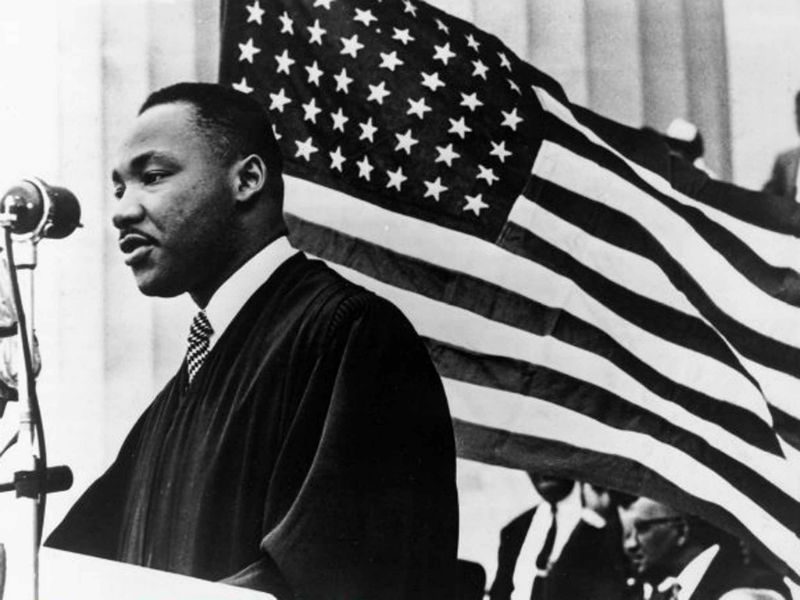

Martin Luther King Jr. | Source: Seattle Times

Martin Luther King Jr. | Source: Seattle Times

“Let’s not kid ourselves,” Cooper said. “The sentiment the president expressed today is a racist sentiment.” Cooper ended his program that night with a deeply emotional editorial about Haiti. Cooper had reported from there during the 2010 earthquake and as he spoke about the courage of the Haitian people, he became visibly emotional and had to stop speaking briefly to control welling tears.

CNN anchor Don Lemon, who, like Cooper, is openly gay, followed suit: “The President of the United States is racist,” Lemon, said at the opening of his CNN broadcast. “A lot of us already knew that.” Lemon, the only black anchor on TV in prime time, has commented on Trump’s racism before. But his disgust was palpable in that statement.

Even the New York Times, which many consider complicit in Trump’s election by rarely calling out Trump’s demagoguery during the two years of the election while laser-focusing on Hillary Clinton’s emails, spoke out.

THIS only took a year.

Or three if we count the primary and election. https://t.co/RD4uTWRXoB— Victoria Brownworth (@VABVOX) January 14, 2018

Yet unsurprisingly, because this is his pattern, Trump simply changed the subject, shifting blame elsewhere. Over the weekend Trump became defiant and began attacking Democrats–who do not hold the majority in Congress–for derailing the immigration talks. But in fact it was Trump’s own words that had done so.

On Sunday night, Trump delivered his most dramatic response yet, telling reporters asking if he was racist,

That, alas, is one more lie from a man whose history of racism dates back to the 1970s when he and his father were investigated by the Department of Justice for racial bias in renting to their building. The Trumps would mark rental applications with a C for “colored” when black men and women applied to rent from them and through controversies including that promotion of the birtherism lie about Obama.

All of this made the counterpoint of the solemn Martin Luther King Day holiday that much more dramatic. This year will mark the 50th anniversary of the assassination of the Civil Rights leader in 1968.

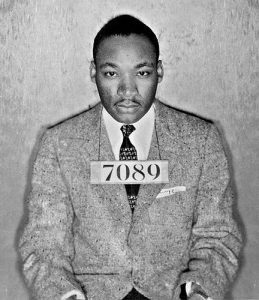

Martin Luther King Jr is arrested by two white police officers in Montgomery Alabama on September 4, 1958 | Source: History.com

Martin Luther King Jr is arrested by two white police officers in Montgomery Alabama on September 4, 1958 | Source: History.com

MLK and Rosa Parks Bus Boycott | Source: Pinterest

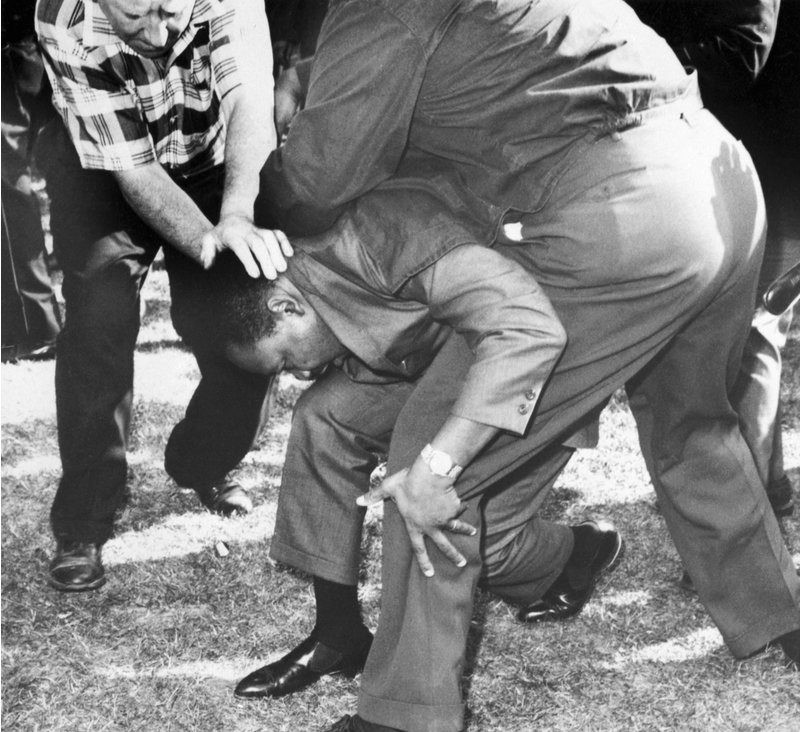

Struck on the head by a rock thrown by a group of hecklers, MLK falls to one knee | Credit: Bettmann/Getty Images

Struck on the head by a rock thrown by a group of hecklers, MLK falls to one knee | Credit: Bettmann/Getty Images

Resistance was a word King used often, asserting that “non-violent resistance” was the most important and vital of tools to fight injustice.

King’s work and words, particularly his essays and speeches have tremendous resonance in the time of Trump. Well before this most recent egregious incident, Trump has attacked women, people of color, Muslims, Jews, LGBT and of course, immigrants. This year for the MLK Day day of service, we should commit ourselves to resistance to hate and to fighting the twin evils of racism and misogyny that infect every aspect of our society and do damage to the majority of Americans.

King’s message has impact for LGBT people who have been under extreme threat since Trump’s election. On December 28, Kerrice Lewis, a young black lesbian, was shot and burned alive in Washington, D.C. Hate crimes against LGBT have risen dramatically during the first year of Trump’s presidency.

Every year I re-read Dr. King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” to remind myself of both what my role must be as an activist and that our oppression as lesbians/LGBT people is not over.

My parents were Socialist Civil Rights workers, so Dr. King was an icon in our home. Through my parents work, I was fortunate to have met some amazing people. (I was far too young to know how amazing they were at the time, but as an adult their names resonated.) I learned activism from my parents and these black women and men as I sat on the floor of our little row house that was filled with cigarette smoke and the smell of stale coffee, stuffing envelopes and watching my father make picket signs and my mother mend clothes that had been given to our church to be sent to Mississippi.

When I was a young child, these people—my parents and the women and men they were fighting for—were risking their lives for justice and freedom. It was a fight that would kill four young black girls, Addie Mae Collins, 14, Cynthia Wesley, 14, Carole Robertson, 14 and Denise McNair, 11, in a racist bombing in the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama on Sept. 15, 1963.

They were older than my sister and I, but they were there in their church that morning, just like we were in ours. And then they were dead. To this day I cannot listen to Joan Baez singing “Birmingham Sunday” without sobbing. (You can listen to her haunting song here, and see a photo array of the girls, courtesy of the Birmingham Public Library Archive.)

Their murders came five years before the same kind of hate would take Dr. King’s life when he was 39—only a decade older than my parents, with four young children, the youngest of whom were the same ages as my sister and myself.

I learned activism in those earliest years of my life. I learned that there were clear parallels between our family, which was poor, but white, and the families of my parents friends, who were black. I was schooled about racism early. I came home from my Catholic school one day and asked my mother what a “n*gger lover” was. I was in the fourth grade and one of my classmates had shoved me, calling me that. “No one wants to play with you, ’cause you’re a n*gger lover.” The slap from my mother was reflexive on her part, I realized a few years later. “Don’t ever say that word in this house or anywhere else again. Do you hear me?” My mother was in the midst of a battle for people’s lives and that word, that awful word, was at the core, emblematic of the violence of those years. She didn’t want that word in our house. But it was obviously in the houses of my classmates.

I learned activism from my parents. Not just from that slap, but from what I witnessed. Activism surrounded me as a child and it was no secret, which is why my parents got death threats and I got name-called and beaten up at school and my parents got arrested in protests. It was not just my parents I learned from, though, but the people who were their friends and colleagues as well as the activist priest at our church. The music that played in our house—mostly folk and protest songs by performers of all races—provided the background to the struggle they were engaged in. I grew up singing songs none of my peers knew because their houses were not like mine, their parents were not like mine.

And there were stories I heard, stories that shouldn’t have existed. One of my mother’s closest friends was a black woman activist from Mississippi. She would stay at our house when she was in Philadelphia as my parents worked on the Philadelphia to Philadelphia Project, a civil rights program they co-founded that linked our northern city with its smaller counterpart in Mississippi.

My mother’s friend was tall–maybe six feet–made taller by the stiletto heels she always wore and her hair piled up on her head in a French twist. Her skin was very dark, much darker than that of my parents other black friends.

My mother’s friend was tall–maybe six feet–made taller by the stiletto heels she always wore and her hair piled up on her head in a French twist. Her skin was very dark, much darker than that of my parents other black friends.

I loved her and I loved when she stayed with us, even though she slept in my room and I had to sleep on the floor in a sleeping bag. She was funny and had a low deep laugh and she would sometimes sing along with my mother to the songs they played and their voices together were so beautiful. But whenever she stayed with us our cat had to be kept in the basement. She was afraid of cats.

One night when she was at our house it was snowing outside and my bedroom had that blue-white light in the darkness from the cast of the snow. We were both awake and I asked her—in the way children baldly do—how she could be afraid of a cat when she was so tall and they were so small.

I heard the intake of her breath. I know now she was probably deciding if she should tell me the truth or make up a story. I know now she was wondering if the eight-year-old blonde white girl lying in a sleeping bag on the floor was old enough to understand what hate can do. She decided to tell me.

It was a simple story, really. Simple, yet horrific. One day some boys grabbed her and put a bag over her. Potato sacking. She was only a little older than me, she said. The bag covered her completely and she couldn’t get out of it right away. She wasn’t alone in the bag, though. They’d put a cat in it. And the cat wanted to get out even more than she did. She was badly clawed and scratched before she could break free.

That was why our cat stayed in the basement when she came to visit us. That story, the murders on Birmingham Sunday, the assassination of Dr. King, being called “n*gger lover” and being punched and slapped at school, sitting on the floor in a swirl of cigarette smoke stuffing envelopes as Joan Baez or Odetta sang in the background. Those are my earliest memories of activism.

A decade later I would be an activist myself, in a different movement, my own movement. I would be expelled from my all-girls’ high school for being a lesbian and I would bear a different kind of witness to discrimination as not one of my lesbian teachers stood for me, not one of the other lesbian students stood for me. I would be put in a mental institution for conversion therapy, a psychiatric procedure that attempts to change sexual orientation through a variety of what can only be termed torture techniques that is still legal in nearly every state. I would soon be on my own and end up homeless for a time, like many young LGBT people unwelcome in their own families.

My activism was forged in those early years in my parents’ house, with black women and men as well as my own parents fighting for justice. It was there I learned to stand up to authority and speak truth to power. It was there I learned that we have an obligation to others. It was there I learned that Dr. King was a messenger and his actions should be a template for all activism.

I re-read Dr. King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” because it’s so instructive. It tells us how to be activists, how to deal with the people who claim to be our friends and allies even as they stand silent as we are victimized. I re-read Dr. King’s speeches and letters to be reminded that there is no simple answer to the question of why some groups are oppressed.

In my early activist years, I was arrested for protests. I was first arrested at 14 and by the time I was 30 I have no idea how many times I’d been taken in for this or that protest. What I knew was that it was essential to fight and protest and never accede to oppression.

Dr. King’s essay, his direct letter to white Birmingham, is not to the racists, it’s to the allies. It’s to the people who were supposed to be fighting with him. That letter has particular resonance now, in the time of Trump, because so many white people are equivocating about Trump’s racism.

It’s time we said it. And it’s time we called out all the isms that are infecting our society. They were there when I was a young child and they are there today. The guises shift, the language changes, but we know that a room full of senators sat silent while the president proclaimed majority black countries and their citizenry “shitholes.”

Dr. King said,

My mentor, black lesbian activist and theorist Audre Lorde said,

We must resist in the time of Trump and that Resistance must be vocal. It cannot be silent. In “Letter From a Birmingham Jail,” Dr. King wrote, “Lamentably, it is an historical fact that privileged groups seldom give up their privileges voluntarily….We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor. It must be demanded by the oppressed.”

For LGBT people under new and ever more dangerous threat since Trump took office, these words resonate. We owe ourselves resistance. We owe our communities of color, of Muslims and Jews, of immigrants, resistance.

Dr. King wrote, “For years now I have heard the word ‘Wait!’…Justice too long delayed is justice denied.” People still fear LGBT people. Trump joked in November that his vice president wants to see us hanged. No one blinked when he said that. There was no outcry, no raft of editorials. It’s still acceptable to joke about killing LGBT people even as Kerrice Lewis was set on fire over Christmas.

Rosa Parks sitting at the front of the bus began the Montgomery bus boycott that Dr. King led. We know now that she was chosen to do this, but we also know that in doing it she risked her life. Every person in the battle for black civil rights in those days risked their lives.

LGBT people may not see the fight for our rights in the terms that black civil rights leaders did. Then again we may. Certainly, the urgency feels as great to me as it seemed to feel for my parents and their friends in the 1960s. Certainly, we have our dead to lament, and the list grows each year, Kerrice Lewis’s name now added.

We must resist. Dr. King gave us the template. I was handed it as a young child and I have used it all my activist life. Resistance, he said, is vital to progress. We know, as he said, “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

Let us fight for that justice, no matter how elusive it appears. Let us resist.