If you asked me a month ago how much I knew about life abroad, I would have described myself as reasonably well-traveled. I would have told you about my stint living in the Czech Republic during my second year of college and detailed the subsequent journeys to Europe in my adult life. As a freelance writer who won’t quite sit still, I’m no stranger to going overseas, picking up in some random metropolitan city, and making my way as I go. What I was unaccustomed to, as a 30-year-old woman who came out at 27, was traveling while lesbian. More specifically, I was unaccustomed to traveling-while-lesbian in Latin America. The experience was all new and two-fold: a vivid, polar-plunge-like reminder that the world still has an achingly long way to go when it comes to Sapphic acceptance; and a visceral lesson in legacy.

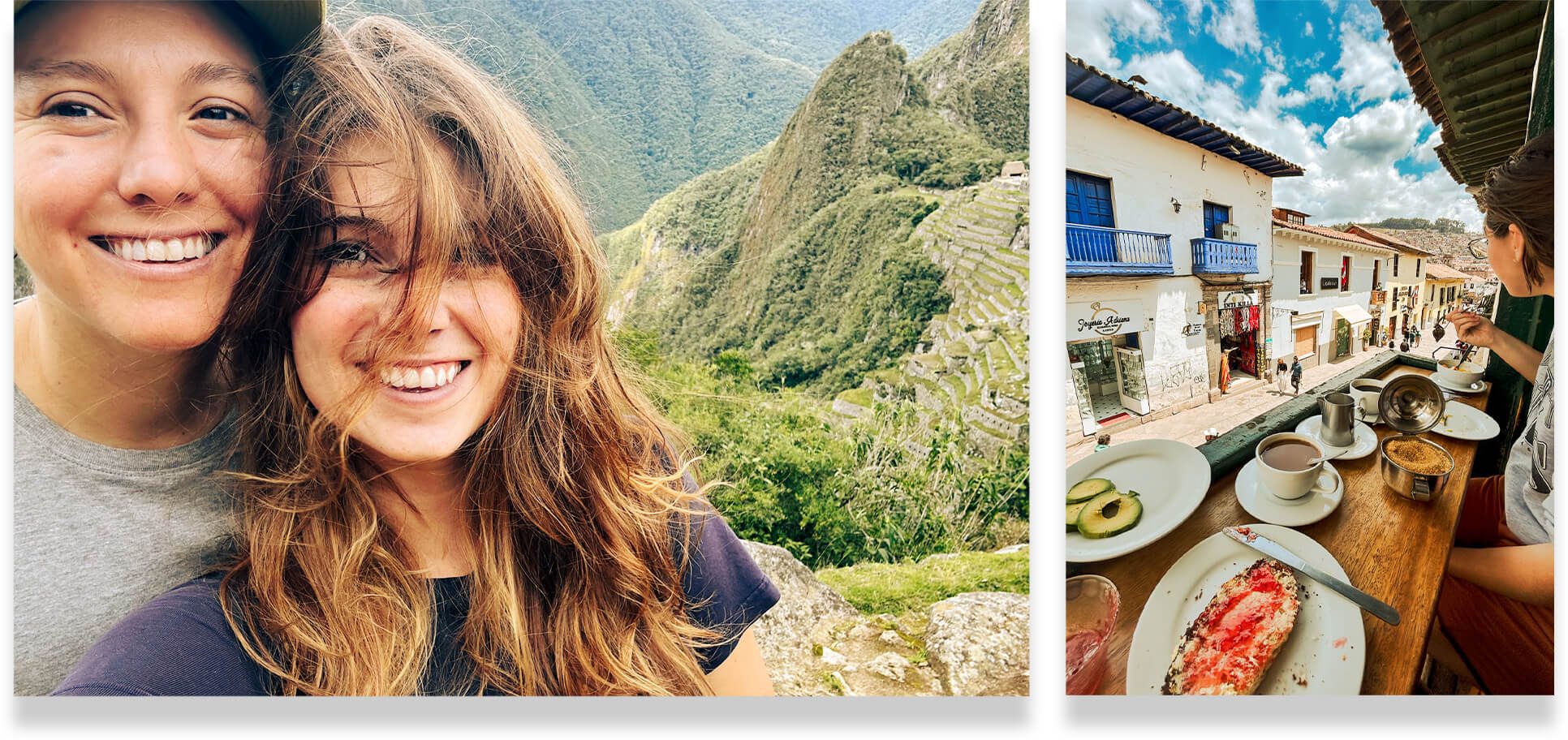

Before I came out as gay, I often traveled with my male partner. Even at the time, the automatic energy and respect given to my boyfriend upon simply walking into a new space boggled my mind. It wasn’t until some time—and some therapy—later that I managed to unpack the fact that my so-called “desire” to be with men was just a desperate desire to stand in proximity to power after a lifetime of having much too little. After this realization and the leaving of my heterosexual life, I traveled alone. Of course, solo travel as a woman comes with its own unique set of worries, but I stuck by my go-to rules (stay in well-populated neighborhoods, be hyper-aware of the surroundings, etc.), and save for the rare uncomfortable situation, I was just fine. So when my girlfriend, Kadin, and I decided to hike one of the wonders of the world and head for Machu Picchu, all we did was give a shout of excitement when we booked the flight, and started counting down the days.

When we landed in Peru, we were driven to our hotel by a man who blared Daddy Yankee and told Kadin (who is Mexican and speaks Spanish) that he could get us anything we wanted. Did we want coke, weed, “a girl”? No thanks. We knocked out and the following morning started on a joyful exploration of downtown Lima. We walked around Parque Central de Miraflores, which was full of stray cats and kitty food in messy dishes, and strangers slowing down as they strolled to take pictures and pat tiny, adorable feline heads. As we walked, hand in hand as usual, we began to notice strange looks from a good percentage of the people we passed by. It was mostly men, but some women too, who looked from our faces to our hands and then back again as though we were a bewildering math problem they couldn’t manage to solve.

After maybe the tenth blatant stare, we acknowledged it to each other and, though we had each experienced occasional homophobia back home in New York (both in the city and in my rural upstate hometown), those instances were the outliers. This situation was the reverse. Most people we interacted with, while not all unkind, seemed to clearly register us in the category of “other.”

“This is probably what it was like to be out in the city in the ’70s or ’80s,” said Kadin with a smile, holding up our hands. “It feels iconic.”

One of the things I love most about Kadin is her easygoing nature. It engulfs her the way the four winds cover the Earth. She is unbothered by petty grievances and lets negativity fall from her the way water droplets roll off the back of a duck. Her response to it all eased me, in turn. These people seemed judgy—but that was all. So fuck it. We kept holding hands; we kissed, and we flirted our way through the local book fair.

At one point, an excited woman, maybe a few years younger than us, approached the bench we sat on with a shy curiosity. She asked if we were together, and when we confirmed, she smiled so wide it cracked her face in half and let all the light inside of her out. Her name was Mila. She was Peruvian, and described herself as bisexual. She doesn’t see a lot of lesbians, she said, and was glad to meet us. She told us about a bar to go to, one that was not openly a gay bar but sort of served as one, and offered a few other recommendations before continuing on her trek to clock in at a local cheese shop. As she turned to leave, she stopped herself. “May I have your number?” She blushed, asking me. “I just love meeting people like you.”

It was during that first evening that things began to shift. We had gone to the elegant Museum of Contemporary Art and were walking the streets of Barranco as the day quickly fell into night. As we made our way down a narrow side street, a group of men saw us, registered our gayness, and looked angry. Not judgy, behind-the-times, lame as hell, like the others did—but truly angry.

We had no option but to walk by them, and before we did, for the first time in our trip, we instinctively dropped our hands, although they had already seen us together. They stared and made their disapproval known in the form of sneers and words neither of us understood, and thankfully it ended there—but so did our sense of safety. Suddenly I saw quite clearly the now-obvious fact that disapproving looks are more than just annoying glares. They are indicators of public sentiment. Being out and proud in a super-Catholic country in which homosexuality is frowned upon is not simply “iconic” as we had thought it to be earlier in the day. It could be, in fact, dangerous.

As we hurriedly tried to find our way back through the dark and winding streets that had seemed so friendly during the day, I heard real fear in Kadin’s voice for the first time in the year and a half we have been in love. We had never before questioned the safety of being affectionate in public or making it known at a hotel that we were planning on sharing a bed. We wondered if it would be like this from now on. We felt like we had fallen into a porthole and turned back time.

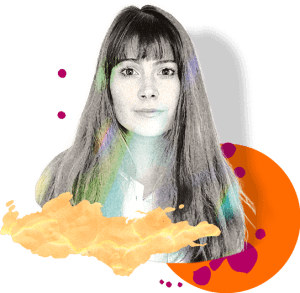

In the morning, we had breakfast at a local spot that Mila had recommended. It was the best coffee I’ve had in all 30 years of my highly caffeine-dependent existence. As we chatted, a warm older woman approached us from a nearby table; our English had made her curious. As we told her our story, she told us hers—she was a Peruvian jazz musician who spent a good amount of time in New York. Without making it A Big Thing, she advised us not to go to certain neighborhoods at night and to avoid other neighborhoods altogether. She gave us the names of these off-limit areas and waited while we wrote them down. It was a sweet exchange, and it wasn’t until long after she was gone that it dawned on us that she had been more than simply friendly; she had been giving us a delicately wrapped warning.

After another day or so, we left Lima for the cobblestone streets of Cusco, the small city from which we would begin our journey to Machu Picchu. We unpacked our bags in our modest but cozy Airbnb and decided to start anew. We walked the narrow and steep streets that reminded us of Europe, and got very excited momentarily when we mistook the Inca flag for our own rainbow emblem. (Later, we learned that the only difference between the Cusquenian flag and the LGBTQ+ flag is that the first has seven colors while the latter has six). We shared delicious and interesting meals, hung out at the Great Square, the Plaza de Armas, and watched a local parade celebrating The Virgin Mary that involved sacrificial lambs. Kadin befriended an elderly Peruvian woman who sat knitting in the road. But like mud in our shoes, the homophobia was ever-present. A creepy dude in a broken-down car slowed as we walked the more residential streets of Cusco, following us for nearly a mile before finally speeding off as we reached a more populated part of town. As we ate outside, a man who looked at us with disgust approached our table aggressively and then receded multiple times as if trying to hide from the view of the restaurant workers. Time and time again, we were reminded of what we so clearly were: Other.

Part of what makes traveling so invigorating is the opportunity it presents to connect with other like-minded people. One of my favorite nights in Paris was spent having drinks at their local dyke bar, La Mutinerie, (which reminded me very much of my beloved Cubbyhole bar back home in the West Village) and flirting with friendly French strangers. In Berlin, queer people take up space in public without apology, much like they do in Brooklyn. These types of interactions didn’t feel possible in Peru, so I was overjoyed when one day at a coffee shop, a gay man approached us and complimented Kadin on her shirt. He was a comedian from Louisiana who had just hiked Machu Picchu with his husband and was sore but full of stories. As he doled out hiking tips, I asked him outright about his experience with the general homophobic vibe. He considered the question for a moment before giving his take: “It’s not great, but it’s better than the rest of Latin America.” He told us about a hotel that catered to gay men he had heard of and postulated that while it was annoying, Peru wasn’t really dangerous. At least, he and his husband had not felt afraid.

I was genuinely relieved for him but also jealous and a bit lonely. I ached for fellow lesbians who knew how Kadin and I felt—at that moment, it felt like we were the only lesbians in the world.

The next morning was The Big Day—the first step in the last leg of our journey, which would culminate in us standing at the top of Machu Picchu, sweating and victorious. We rose early to board a rickety bus that climbed the steep mountains of rural Peru at an aggressive pace. We drove through farmland and small villages and the picturesque Sacred Valley, ultimately landing in a small town from which we could catch a train that would terminate at the town of Aguas Calientes—the closest village to the great mountain we had come all this way to scale.

And scale it we did. The next morning, we woke in Aguas Calientes and anxiously began our climb. Each peak we reached I thought could not possibly be surpassed until it was. Until we reached the very top, where the Inca people held ceremonies, believing that being so high up brought them closer to the divine. As we stood at the summit and looked down at the tips of mountains that themselves were embedded in clouds, I understood why.

We kept going and hiked the Inca Trail, which ended at a sacred place at the very end of the rocky terrain where Inca leaders would pray to the gods that the Spanish would not conquer them. (In the end, the Spanish did conquer them, but due to its extreme remoteness, being hidden in the vast expanse of such great mountains, they never found Machu Picchu itself, so in a way, maybe their prayers were answered.) It was like nothing I had experienced, with all the hiking I’d done from the mountains of Montana to the open plains of Greece. It was like the mountains were talking to each other, continuing some ancient and eternal conversation, and we were mere mortals on the sidelines, witnessing their exchange for the briefest moments.

On the long trek back down the mountain, the two of us fell silent, as people do when they are stunned by some great thing that is both outside of themselves and also, somehow, now within themselves, and I came to realize that at some point over the course of our two-week trip I had been changed. I found myself considering things more deeply than I ever had. Seemingly small things, like the origin of the phrase ‘chosen family’ for instance—the term that was coined because it was so routine for families to reject their kin when they came out that queer people were forced to choose families of their own. I had known that but had never really sat with it.

Of course, homophobia knows no borders. It is everywhere, New York City included. My own coming out was not a walk in the park. But the laws are on our side. And negative experiences are the outliers now, thanks to the brave women who paved the way. Things are getting better, so much better that sometimes the ease of out-and-proud living in Brooklyn is something I take for granted without even realizing it.

But in Peru, at the tail end of 2023, I was reminded of the facts, and I will spell them out for you here: in eight countries, there is a death penalty for being gay. In 76 countries, there is anti-gay legislation on the books, and even in the United States, anti-gay violence and anti-gay legislation are on the rise.

I realized, on my journey home, that I would never again glorify what it must have been like to be out in the ’70s, ’80s, or ’90s—how utterly badass it would have been, how gay bars were true havens of community, the imagined romance of everyone having to band together against society at large. I would never again wish I could have joined the infamous activist group The Lesbian Avengers, which formed with a mission to fight homophobia in New York City before I was even born. Instead, I would only revere the women that came before me for having the courage to do what had never been done, and commit myself to joining their ranks.

About the author

Madeline Anthony (she/her) began her career in journalism where she reported at various outlets throughout New York City including The United Nations Press Corps, NewsCorps, and The Brooklyn Paper. She now works as an editor in the publishing industry and writes fiction in her off-hours, gladly trading time in the real world for imagined realities. Born and raised in rural upstate New York, Madeline lives in Brooklyn, where she can be found getting lost in existential thought loops, painting, advocating for reproductive freedom, and unapologetically advancing the gay agenda. She is currently querying her first novel.

What the phrase ‘lesbian visibility’ means to me

To me, lesbian visibility means queer women being accepted as the rule and not only the exception. It means living truthfully in unapologetic joy.

Social handles:

TikTok @gaygirlonline

Twitter @maddielinea