Curve editor Merryn Johns reflects on a female photographer whose work possibly altered the course of her life, and discovers that they share a female gaze across hemispheres—and a love for Vegemite.

Images by Dona Ann McAdams.

I first discovered the photography of Dona Ann McAdams when I was a theatre student in Australia, leafing through journals looking for examples of feminist and queer performance art. It was the late 1980s, early ’90s when the only way to find other queer women artists and activists was at a bar or a march. Before the Internet, if you wanted to know what was happening to minorities in other countries, you either went to the library or to the airport. I was 10,000 miles away from New York City, but McAdams’ images put me right there—and, in a way, probably actually led me to Manhattan, eventually. Little did I know it until I interviewed McAdams about her new book, Black Box: A Photographic Memoir, that Australia had been as meaningful to her; she had traveled Down Under in the 1970s to join the anti-nuclear movement at a time when Aboriginal rights, women’s and gay liberation, and politically progressive art such as the animal-free Circus Oz were on the boil. Perhaps there is a shared visual language among queer women across hemispheres and cultures—an understanding that the female gaze and physical presence can hold space across all dimensions. So I tell her about the influence her images had on me.

“Your country of origin was extremely influential to me as a young artist,” she says. She describes powerful activism during her Southern sabbatical; encounters with feminist collectives and street artists; aesthetics and tactics she took back to the U.S., and which she says “we could use more of today.” Plus, she developed “a keen taste for Vegemite. I always have a jar on my counter at home!”

And so here is some of our conversation—me in NYC and McAdams in Vermont on her goat farm.

How do you identify (LGBTQIA+), and how has it changed over the years?

DONA ANN MCADAMS: From the first time I saw Mary Sue O’s white bra at a sleepover at my house as a kid, I knew something was up. My best friend in high school came out to me while we were working at a department store, folding clothes. Gilbert O’Sullivan’s LP had just come out, and he was wearing a shirt with a giant “G” on the front. We could see the album cover across the aisle in the record department from where we were standing. Karen said: You know what that ‘G’ stands for, don’t you? I said, Yeah, do you?

So I’ve always loved women. If I had the language back then that we have today, I would have identified as pan-sexual. That probably best describes who and what I love. It’s the person, not the gender. I’ve had girlfriends and boyfriends. I’ve been married to men, and had a civil union in New York City with a woman before there was legal gay marriage. I met my life partner later in life; he happened to be a man. We had a tremendous amount in common, and we worked well together—and he is not exactly what anyone would call “hetero-normal.” So I don’t think my identity has changed. I work in black and white, but there’s a lot of grey in the world. The words have changed, but not who I am or who I choose to love.

How was Black Box: A Photographic Memoir written? Did you sit with the images first until the memories came, or did you recall the people, places, and events and then go searching for the photos?

I started writing these stories down on a lined white pad with a lead pencil. I think I’d been doing it for a while, writing in the darkroom between the Permawash and the wash. But after my brother Tom died in 2013, I became more serious of the notepad. See, he was the keeper of our young selves, all things from our childhood before I moved away to San Francisco. I think I was writing them to remember. Then, the stories branched out of my childhood into my adult photographic life as an artist and activist.

Around the time of the pandemic, I started to put the little stories, which I called ditties, on social media. At the same time, I was mining my archive, because for the first time, I didn’t have a real job aside from making my own work. Sometimes the photographs I’d find would spark a memory. Sometimes not. When I went to Yaddo, the artists’ colony, in 2021, I stuck some of the stories with photographs on the wall to see what would happen. I showed them to other artists, strangers from many other disciplines. This group of thirteen artists thought they had potential, and I began to work with the idea of the stories working somehow with the images. I wanted the stories and images to work on their own, the stories not to be a caption for the photograph, the photographs not necessarily from the same time period in which the stories took place. But the two had to work independently of each other, and if they spoke to one another, all the better, but not literally.

The sequencing of the stories and images really started to take shape with help from friends, then one day I got a DM from Mark Alice Durant at St. Lucy Books asking me what I was up to. I knew from the start I wanted him to publish the book because he made such wonderful books and gave me a lot of creative control, and it was great working together.

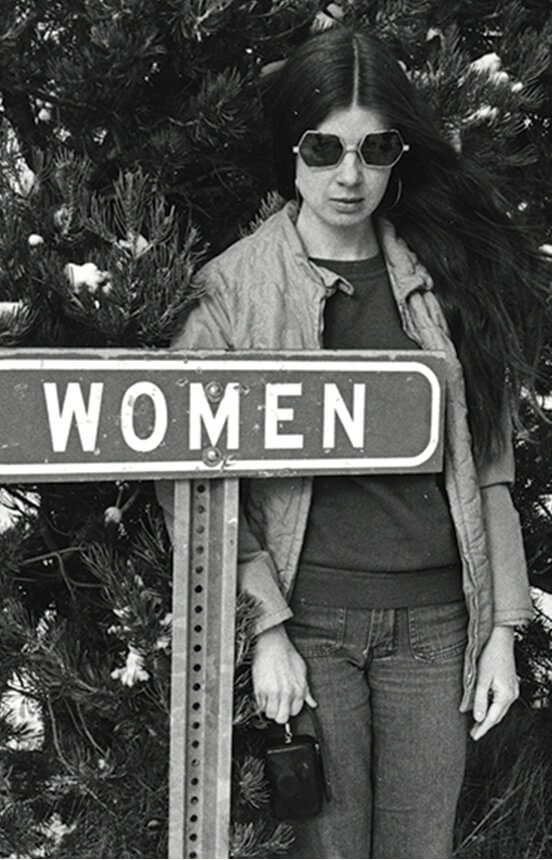

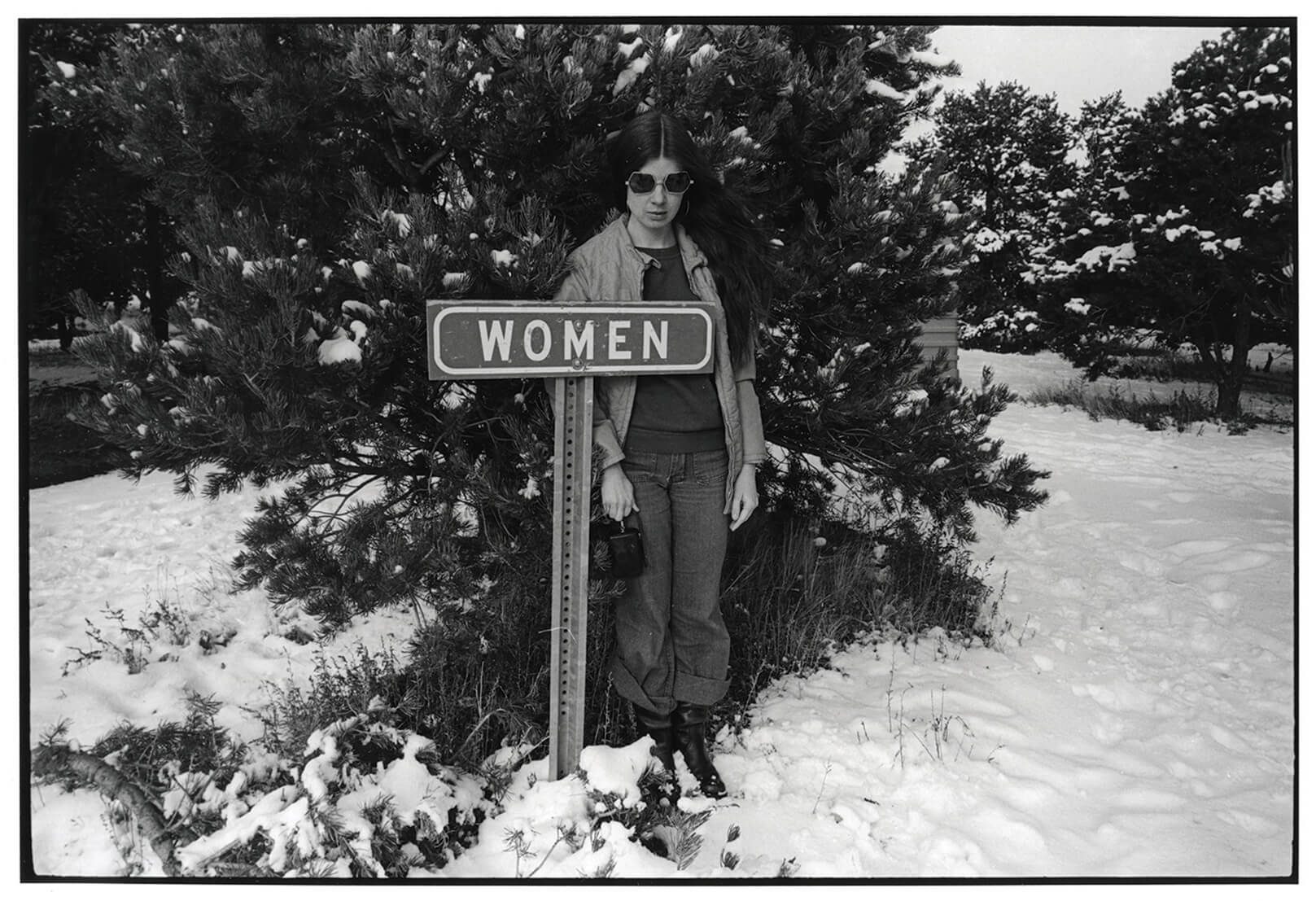

“…I always looked. Especially at women. As long as I can remember I was fascinated by how they presented themselves in public. The dresses and make-up and all the women stuff I didn’t understand. Everyone knew about the male gaze, but the female gaze interested me more. Women looked at women all the time. And not just a certain kind of woman, but all kinds of women. Every one of them. I photograph women because I love them and happen to be one.”

Can you tell me what you go through when you take a photo?

When I’m out with my camera, which is whenever I’m out, something will stop me. I’ll get a feeling. Something catches my eye, a quality of light, a landscape, an event about to unfold. I lift my Leica with a sense of something about to happen—someone might walk in the frame, a tableau, or wait for a horse or person or car to run by, and two people to meet in the space and wait and know it will come. Sometimes it just happens. I don’t have time to think. I’m always aware of the changing light and being ready and present, because when you’re shooting analog, you don’t have time to see if the exposure is right. My camera is always set with the right exposure, shutter speed, the right aperture.

I use the depth of field so that anything from 4 to infinity is in focus. Sometimes I’ll focus because I want to shoot something in the foreground or background or center of the frame, or vice versa. These are all intuitive decisions. Muscle memory. Mechanical. I’ve been doing it so long I don’t have to think. Fifty years of instinct. I press the shutter, advance the film. Take one or two photos. I might move left or right, and often when this happens, I know I made something that is interesting, or maybe even a good photo. Many times, these moments fail. When I process the film and look at the 36 exposures on the contact sheet and I’ll go back and look at the five or six I thought were good at the time. Sometimes I’ll know it on the spot.

Is there a female gaze? Is there a lesbian gaze?

For me the only thing that exists is the female gaze or the “lesbian gaze” or maybe even the “queer gaze” because that’s the way I look. I’m all those things. I’ve experienced men looking at me, and I know what that feels like, and it’s not good. But now that I’m a crone, it doesn’t happen so much anymore. And I hope I’ve never looked at anyone that way. Reading Laura Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure in Narrative Cinema” was a revelation for me. I can’t speak for anyone else, but I can say I look at women because I love them, and because I am one. I do think, to use your language, there is a type of “lesbian gaze” where two women share the looking and know why they are looking and what they are looking at. This type of gaze is often accompanied with a smile or a nod.

One other thing: As a woman and as a photographer, people very rarely pay attention to me. I’m often invisible.

The late ’80s and early 1990s were when I first saw your work with the WOW café and PS122. What was happening on the Lower East Side in New York City for lesbians and queer women?

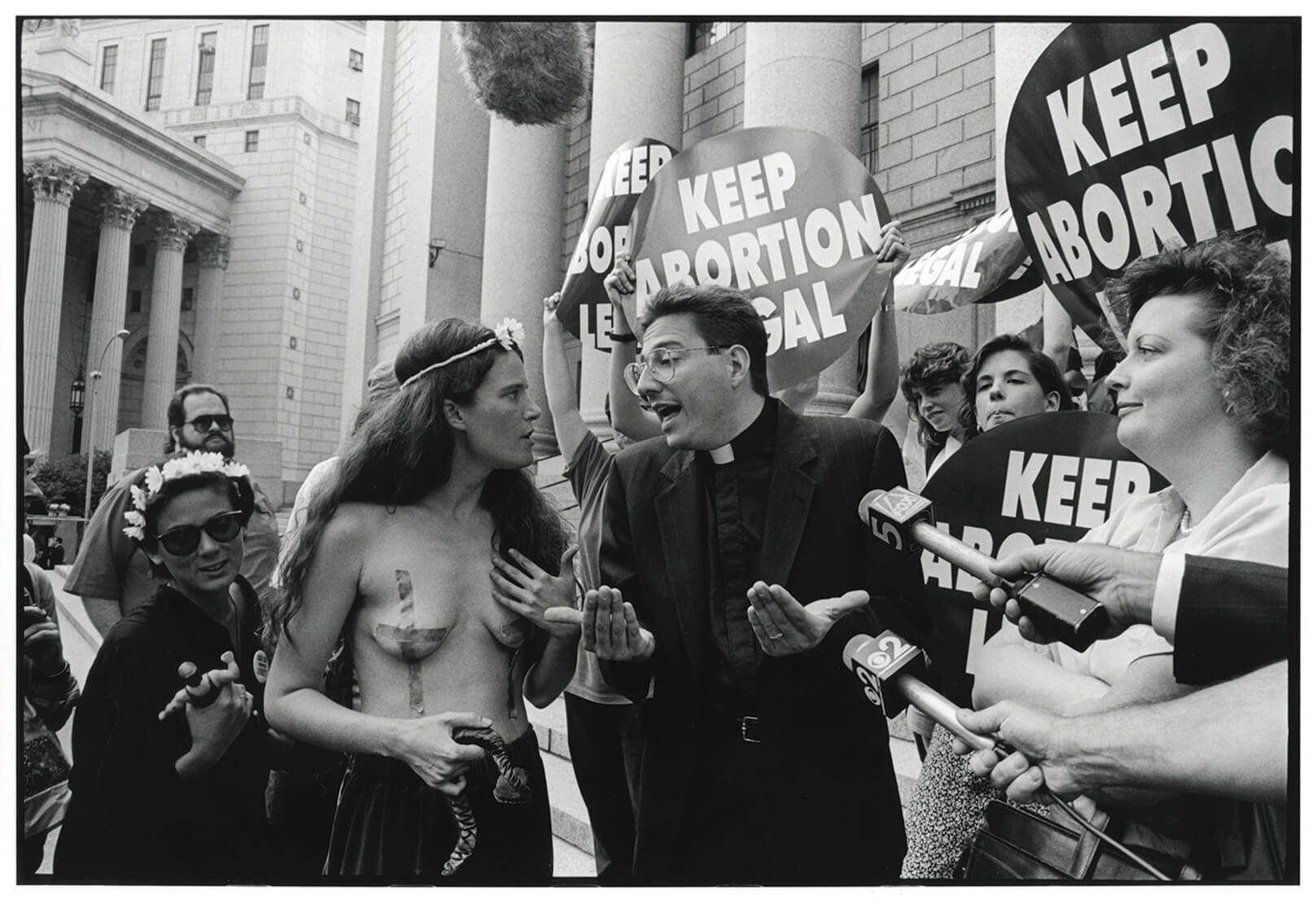

As soon as I arrived on the Lower East Side, I quickly found my way to PS122, and shortly thereafter, the WOW café. I have a piece about the WOW café in Black Box. It’s the place we went to celebrate women and women’s work. There were bars like the Cubby Hole, Meow Mix, the Dutchess, but I never hung out in bars. My community was based in the theatre. The Lower East Side was a hotbed of art and activism. There was 8BC, the Limbo Lounge, The Pyramid Club, King Tut’s WhaWha Hut, Club 57, Lucky Strike, and small art spaces like the Fun Gallery. My community was also on the street protesting for abortion rights, access to health care for women, and then queer men because the AIDS crisis took over our lives. ACT UP. The Women’s Action Coalition and many subsidiaries. There was the Lesbian Avengers. My camera was my ID, and it allowed me to move fluidly through many communities and participate in an active and documentary way.

The culture wars of that time, when lesbian and queer artists such as Holly Hughes were defunded, are they happening again?

The culture wars never really went away. There’s always been censorship in the arts, only now it’s clear and out in the open, and everyone can see it, as it was in the ’90s. In the ’90s, we spent a lot of time in the street and taking buses to Washington to protest. I’m hoping the current protests are going to manifest themselves.

I really want to know your thoughts about iPhones and digital technology vs. analog photography.

I have an iPhone. I’ve had one for years. I make pictures with it. But to me, it’s like a Polaroid camera. Fast, dirty. Quick. For me, working with an analog camera, working with film, with black and white, my love and passion for it hasn’t changed since I picked up my first Leica in 1974. I’m interested in the abstraction of black and white, light and time. There was never a point when I was remotely interested in shooting in color, perhaps because my real influence is illustrations. Line drawings. Pen and ink, Cartoons from the funny pages, especially Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy, who I adored.

For me, photography is about being in the moment, in the present tense. With an iPhone or digital camera, it seems you’re always checking immediately what you’ve just shot. How could you not? So you’re never really in the present. You’re in the past or the future, but not there in the moment. Also, something magical happens with analog in the time between making a photograph and processing it. It’s similar to what happens with memories. The moment sits in the camera, in the roll of film, and you may not process it for a few weeks or a month, or in my case, sometimes, even a few years. It lies there in the silver, and when it comes to light, when you process it, you’re already in a new place and can see it differently. I love the gap of time that happens with analog. Time is frozen on a contact sheet, on a negative.

I remember in 2006…People were making the move to digital. Easier, faster, cheaper, but I made the conscious decision to carry on with analog, and would continue to shoot film as long as I was able to get it…and if for some reason film and paper and chemistry were no longer available then I’d had a really good run up until that point…over thirty years.

I think digital photography and the iPhone are very important because everyone has the opportunity to take their own photos and record their own lives, especially now when witnessing is as important as ever.

Example of an early photo you took where you knew you were a photographer?

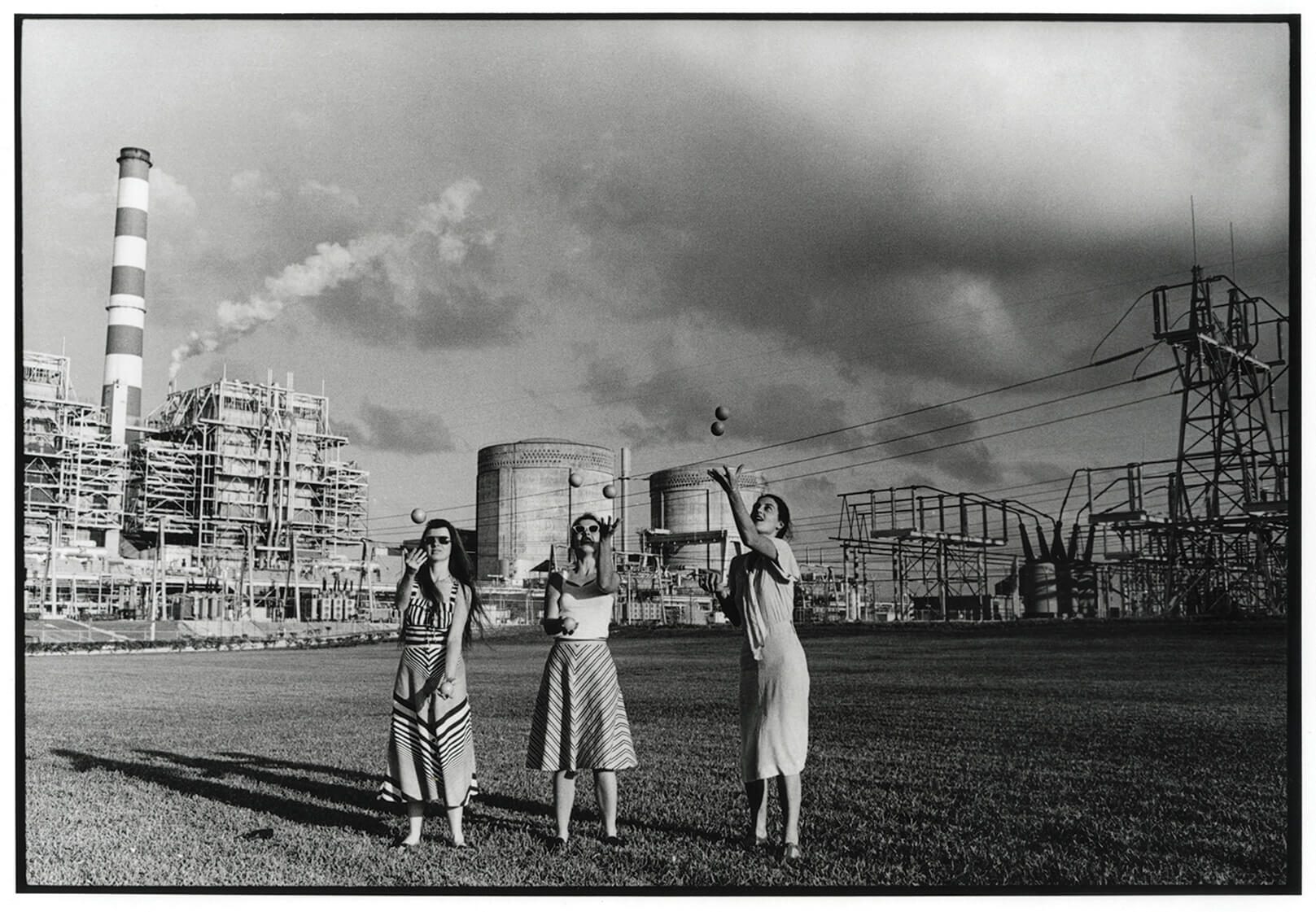

The three women juggling in front of a nuclear reactor, which I staged, I knew. I used to think to myself: Will I ever make another photo as good as that? But at a certain point in my life, those things cease to matter, the wondering, the thinking—it just is.

What are you currently working on?

I’m working on a portfolio called “Searching for Sheela.” If you’ll excuse the expression, I’m essentially photographing “stone pussy,” by which I mean, medieval and older forms of vaginal imagery, the ancient Sheela na gigs found at sacred sites and hidden in church architecture and at various historic monuments all over the world, but specifically in Europe, and even more specifically in Ireland. The Sheela na gig is a figurative carving of the naked female form displaying an exaggerated vulva. They’ve been around since prehistory. They often accompany places of feminine power. I’m going on a pilgrimage to find them in Europe and Ireland. The project is a kind of bookend to a similar one I did in my early twenties when I drove across the country photographing nuclear power plants, and often putting myself in the picture. The Nuclear Survival Kit (1980) was my own wry critique of the man-made nuclear power industry and its dangers. “Searching for Sheela” is my celebration of women’s generative power.

Visit Dona Ann McAdams’ website here. Get her book Black Box here.