The first thing to know about Phranc is that she’s low-key funny all the time, introducing herself as “Phranc—with a PH and a hard C.” She’s what the French call droll. Phranc has a dry, clever, not-ostentatious wit that just pulls you along through much of what she says and it is, to be honest, delightful. Phranc is delightful. She’s smart and savvy and talented in ways you won’t expect and is exceedingly inquisitive about everything. She’s totally immersed in her current work and excited to talk about it and the journey it took to get to it. She embraces a multiplicity of communities from punk rock to folk music to feminist to Tupperware. (More on that last, later.)

And she’s gay. Phranc is so totally, irrepressibly, no-holds-barred gay. She discovered her butch self back in the 1970s and never looked back. She “pretty early on figured out I was a lesbian” and so then it was “just trying to get out of the house as soon as I could.”

Phranc says she “dropped out of high school to be a lesbian.” In an interview for the Women of Rock Oral History Project, she says she was “a young butch trapped in a nuclear family.” Now, a half-century since she came out to her parents and “they didn’t like it,” Phranc still loves being a lesbian. In this fraught political time when orientation and identity are both under threat from the GOP and often attacked even within the LGBTQ community itself, it’s refreshing as hell.

Three decades after Phranc was interviewed for Deneuve’s debut issue, the artist, performer and lesbian icon is continuing to write new chapters of the book of her life. Phranc the artist—like Curve itself—is in a wholly different place. The latest iteration of Phranc’s story is a memoir in paper: a multiroom gallery art installation made of paper that Phranc crafted called “The Butch Closet.” The retrospective exhibition presented her acclaimed artwork and ephemera to celebrate her groundbreaking life and introduce her to a new generation of fans.

In an exclusive, wide-ranging Zoom interview with Curve, Phranc talked about The Butch Closet, her work and her music. She told Curve that “a lot of my peers have really wonderful literary memoirs coming out,” but that she didn’t want to write a literary memoir, and so this is a “different kind of memoir on paper.”

Phranc also wanted to “explore the metaphor of the closet. But she’s “always been out” so that meant a re-vision of the closet. Phranc’s vantage point on the closet was a re-imagining. She explained that a closet isn’t just someplace to hide, “the metaphor is also a place to grow and get ready and be safe. It’s a place to store all your precious things.”

As one enters the art installation, Phranc says, “You’re literally entering my closet.” There are clothes made of Kraft paper on hangers that must be pushed aside to enter the space. Imaginative doesn’t begin to articulate how dynamic the concept is.

In rethinking the closet as part of her memoir-journey covering her musical and artistic career, Phranc put together the show, which debuted in October at the Craig Krull Gallery in Santa Monica, California and ran for six weeks through early December. She’s taking the multimedia show on the road and it will be popping up throughout the U.S. in 2024, celebrating 40 years of her groundbreaking music, activism, art, feminism and of course, butch identity.

Phranc has spent years working on the project and the result is the story of her lesbian life, the culmination of her journey as an artist with an interactive message about being out and proud in a world that devalues queer, lesbian and butch identity every day, a world in which “don’t say gay” is an edict and a law in many places.

Phranc is most associated with the music she’s been performing since she landed in the Los Angeles punk rock scene of the late 1970s and 1980s. In those years she performed with her first band, Nervous Gender, as an androgynous butch with a bleach blonde crew cut and men’s clothes. She moved on to the group Catholic Discipline and Phranc appears with Catholic Discipline in the 1980 documentary The Decline of Western Civilization. She performs in the 1981 film Madame Wang directed by Andy Warhol acolyte Paul Morrissey, and is credited there as Phranque. She also inspired the influential Queercore music movement.

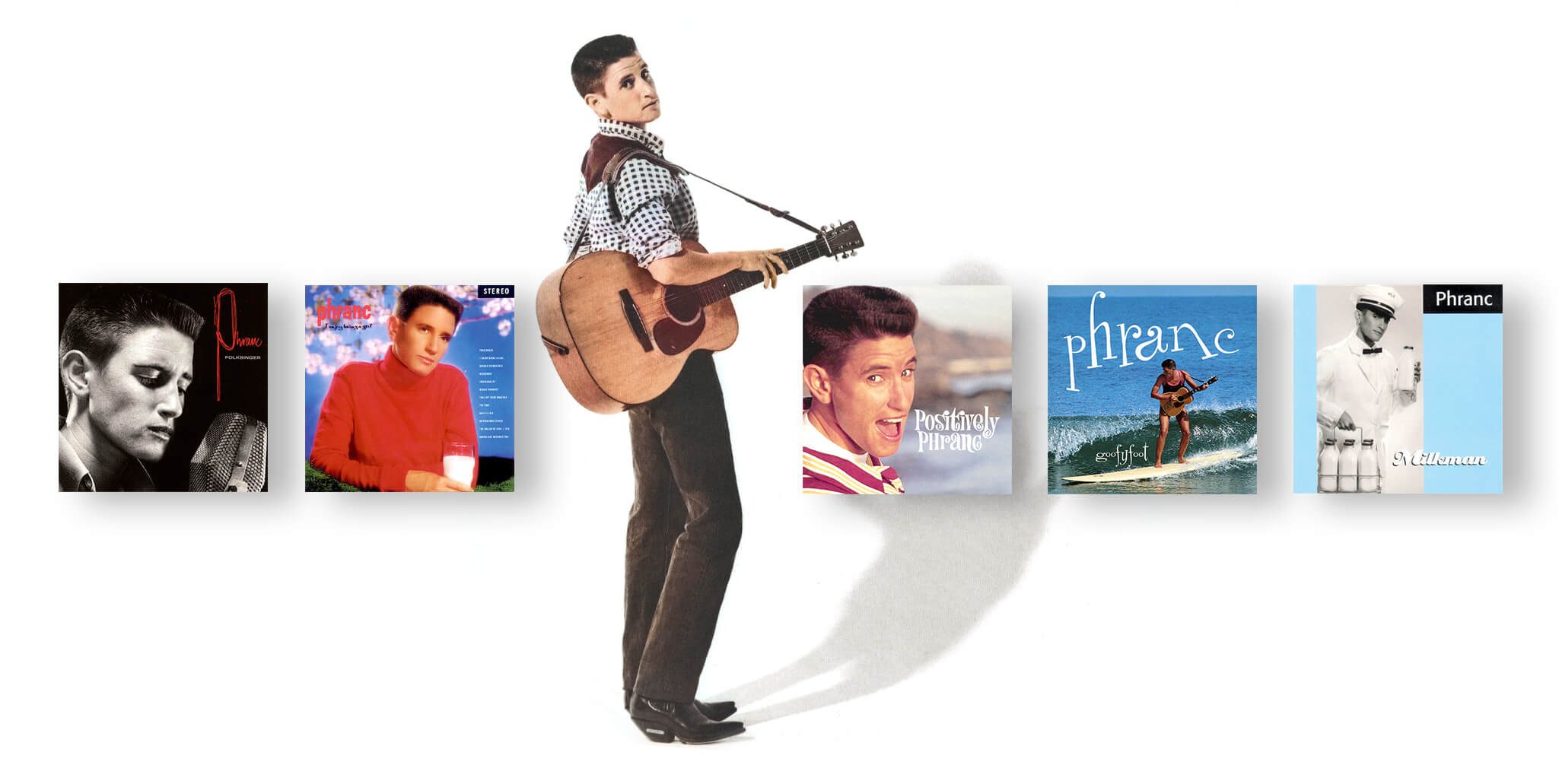

In her next iteration in the late 1980s and early 1990s, performing with The Go-Go’s Elissa Bello and others, Phranc defined herself as the “All-American Jewish Lesbian Folksinger,” and opened for the hit groups The Smiths, Hüsker Dü, Violent Femmes and Billy Bragg. A series of albums followed, including “I Enjoy Being a Girl” in 1989, “Positively Phranc” in 1991, the EP “Goofyfoot” in 1995 and “Milkman” in 1998.

In Los Angeles, on January 11th, 2018, Phranc performed her song “Lifelover” for a fundraiser for the Women of Rock Oral History Project. She told the crowd that she wrote the song at a time when she “wanted to kill myself, and I’m still here.”

Phranc says, “Coming out saved my life. I was a suicidal teenager and so many of us don’t make it, because they can’t get through that door”—the door out of the closet.

Bringing back butch

From that world to now, Phranc brought her memoir, more music and a fresh argument for butch identity and solidarity. Curve spoke with Phranc about the “trending away from butchness and butch identity” and that the anti-butch rhetoric is being promulgated in part by the breadth of GOP politics and policy about queer and trans identities.

With her flat-top hairstyle (she notes that she’s been going to the same barber for 30 years, but that the barber is 82, so she’s interviewing new flat-top barbers), white crew neck T-shirt under a black and red checked flannel shirt, Phranc is quintessentially butch. And she said her experience out in the world as a performer and artist was opposite to any trending away from butchness.

Butchness is trending.

“When I came out in the 1970s, butches were recognized,” Phranc says, “but it was a period of lesbian feminism and butches were seen as old school. Butch wasn’t really honored back then.” She says as a “baby butch”—and makes air-quotes with her fingers—at that time it was different and that now “there’s been a huge reclaiming of butchness.”

Phranc says traveling in the U.K. in the 1980s “there was always a strong butch contingent,” and talks excitedly about the British butch poet Joelle Taylor “in her three-piece suits” and photographer Roman Manfredi, whose “We/Us” is a “photography and oral history project which centers Butches and Studs from working-class backgrounds within the British Landscape.” Phranc says she wishes Manfredi would bring her work to the U.S. and adds declaratively that both women’s work is indicative that “I’m seeing more positive butchness.”

She explains that “there are all these Instagram accounts like Butch Is Not a Dirty Word where they honor all these different butches of every ilk, of every style. And then there’s Butch Hair Quarantine which was started by Karen Thompson during the pandemic, which honors butch style. And then there’s the Butch Boudoir Project. So I see a huge, young butchy, dykey population really honoring the butch identity.”

Phranc says, “I’m kind of thrilled with that. I came from kind of a butch backlash, but I’ve been doing the bulldagger swagger for a little while now and now I’m finding there are many more of us dancing to the same tune.”

At the heart of her own “positive butchness” is Phranc’s show and her music, all of which are rolled together as both memoir and new work. Phranc’s solo music has just been released on major streaming platforms for the first time. This includes her critically acclaimed first solo album, “Folksinger,” which she explains she funded by working as a lifeguard and which pivoted her out of the Santa Monica club scene and into the national and international spotlight.

Among the re-released work is “I Enjoy Being A Girl,” which features Phranc’s iconic song, “Take off Your Swastika.” That track was written in reaction to punk violence and use of the swastika by fellow punk artists when she came to the scene “with such a strong identity and foundation.” But as she said to Curve, that song has taken on new messaging for her as a Jewish lesbian in this period of extreme antisemitism.

Lesbian lifetime guarantee

Phranc, 66, has had a multiplicity of identities over the past four decades as her work and her life have grown and changed. While most fans think of her solely as a musician, her work as a visual artist has run parallel to her music and intersected with it. She’s been making paper sculptures as what she calls the “Cardboard Cobbler” for 30 years, using scraps of cardboard she collected in alleys and recycling bins, as well as rolls of Kraft paper. The objects she created were replications from her own life: she’s been telling this visual story for years, just as she’s been making music.

In 2007, the New York Times reviewed a show of Phranc’s at Cue Art Foundation, the pieces chosen by singer and writer Ann Magnuson, and notes: “Dress shirts, T-shirts, combat boots, a life preserver, motorcycle jacket, barbells, bandanna, picnic basket or sailor’s cap skillfully made from paper or cardboard recall Claes Oldenburg’s ‘Store’ or Warhol’s paper clothing. Phranc’s treatment of Eisenhower-era objects is loaded with subversive significance, however, since many of them functioned as signifiers of gayness in a heavily closeted period.”

Similar pieces are curated in “The Butch Closet,” about which LA Weekly wrote, “Whether the message is that queer people can still dig Americana, or that re-invention can manifest in many kinds of dimensions, or that magic can be found in the commonplace and made from nothing, or that activism can take as many paths as self-discovery, or simply that being yourself is its own reward—really, it’s all of the above—Phranc is a melodious and inventive messenger.”

The story these pieces tell is declaratively lesbian as well as uniquely Phranc. The Bulldagger Belt. The combat boots. The red bandana. A string of flags titled “Junior Dyke.”

The only thing missing is Tupperware. “To make a living as a musician, you have to be on the road,” says Phranc. So she took a job as a Tupperware demonstrator and manager to be closer to her partner and two young children. She became the Tupperware queen, selling Tupperware at parties throughout the early 2000s.

The 2001 documentary film, Lifetime Guarantee: Phranc’s Adventures in Plastics, directed by Lisa Udelson, chronicled Phranc’s side hustle as a best-selling Tupperware maven in her bow tie and flat-top. While the other Tupperware ladies accepted her, at the Tupperware conventions, the film shows, she stood out, occasionally being mistaken for a man and often raising consciousness.

Dressed in a suit and mistaken for a man at one convention, she responds gently, “I’m actually a girl, I’m just dressed up tonight.”

“Tupperware,” explains the lesbian-feminist Phranc, “acknowledges women in a way that’s very special. You’re self-sufficient, making great money…It really builds self-esteem. I have seen some of the shyest women become exuberant.”

From coming out at 17 and interning at Lesbian Tide magazine and working at the Woman’s Building, the Los Angeles landmark hailed as the nation’s first female-owned and -operated community center for feminist art and education, to being a world-touring out butch woman, Phranc’s history has been singularly lesbian since the day she decided to “drop out of high school to be a lesbian” and drop into a lesbian-feminist consciousness-raising group where the mostly older women made peeping sounds when she said she “liked chicks.”

Phranc’s irreverence and wit and work have kept her on our radar since that first interview three decades ago. But her message runs deep. “The reason I’m doing this work, the reason I’m out on stage, is our lives are at risk, you know?”

“I want to be the person who’s out there,” she says. “There were people who were out there for me. If I had come out and there was no community, no arms to fall in, I wouldn’t be here. So it’s important to acknowledge it’s not easy, but it’s very, very important and worthwhile to come out, so—come on.”

View more of Phranc’s work here.