In a world of seemingly endless digital offerings, three millennial women have founded WMN, a zine of substance by and for people who identify as lesbians.

Living and working in New York City, the founders and editorial team are, however, from other places: Florencia Alvarado is from Venezuela, Sara Duell is from Sweden, and Jeanette Spicer is from Maryland—a geographic scope which helps give the publication its wide-ranging, all-embracing worldview in addition to the mission to give visibility and expression to underrepresented lesbian groups.

With four issues behind them and another about to be released, diversity is truly on display in this periodical which has been referred to as a zine but which is more substantive than that. Epistemologically speaking, a zine is a DIY, small-circulation, self-published work sometimes featuring appropriated and altered texts and images along with work by its makers and friends. But WMN is much more expansive than that both in method and medium.

Providing a hard copy space

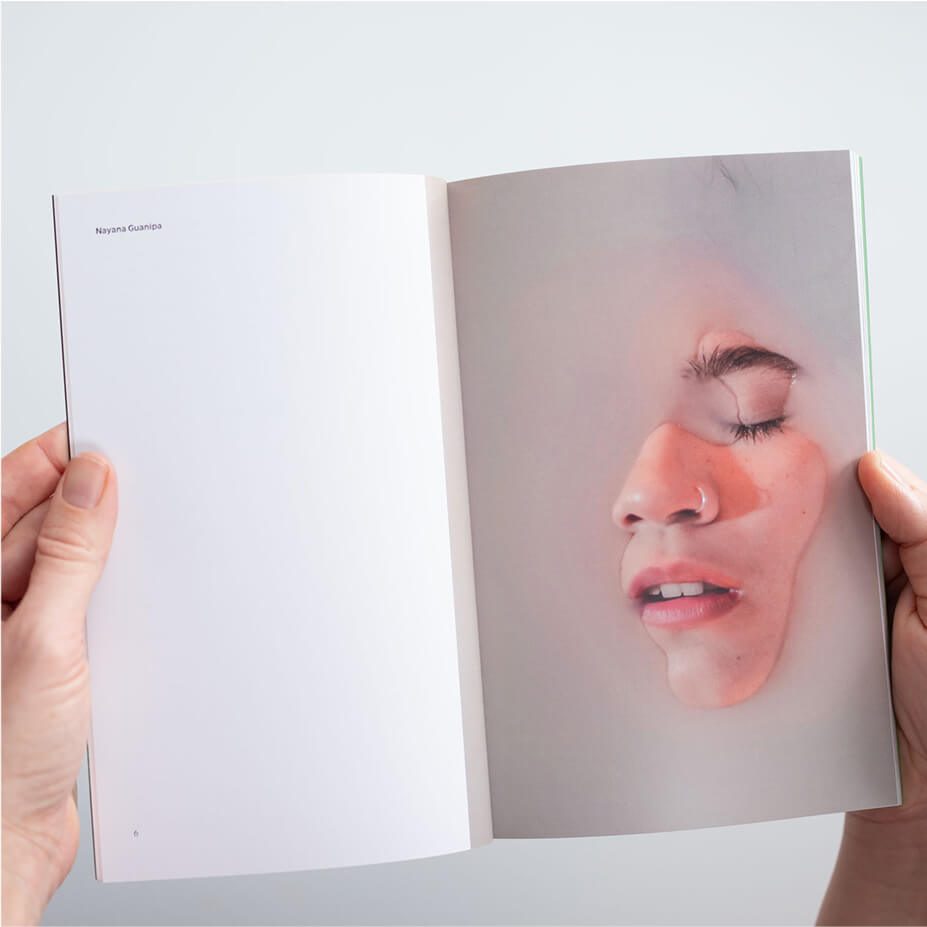

At 80-plus pages, and with beautiful design and layout befitting book publishing, WMN artfully curates diverse work from open calls for submission from specific lesbian groups. Issue One, fabulously titled Seasons of a Dyke spotlights the work of rural and smaller city lesbian artists and poets; Issue Two boldly titled Show Me What You Got invited submissions from older generation dykes; Issue Three is meaningfully titled Taking Space and focuses on disabled and chronically-ill lesbians, often invisibilized by communities; and Issue Four gives voice to the experience of immigrant lesbians and refugees. The Fifth Issue is currently in production and will represent lesbians who identify as non-cis.

Millennials have long been labeled as the most tech-savvy generation, so why did these three women, born in the 1980s, revert to an ambitious, print periodical for lesbians now?

“Without undermining past and present lesbian art and publications, they felt that there wasn’t a lot of current lesbian representation tangibly available, especially made by lesbians themselves.”

The idea was formed when Duell and Spicer discussed the ongoing lack of lesbian representation in general. Without undermining past and present lesbian art and publications, they felt that there wasn’t a lot of current lesbian representation tangibly available, especially made by lesbians themselves.

Lesbian representation is “so small in comparison to the canon of art history,” says Spicer, who has a background in visual art. The Lesbian Bar Project and the Addresses Project, while immensely valuable, in many ways underscore the gradual erasure of a physical community which lived or gathered in bricks and mortar and located each other in designated spaces. Alvarado, Duell, and Spicer’s idea was to use a periodical as a kind of space in which lesbians from all locations could meet and mingle in discourse through art and poetry. And when each issue is released, they can meet in person, too, at the launch parties.

Spicer says the question was “how could we create something physical that would be long-lasting and archival for people to have at home and in libraries and bookstores.” Duell notes that some of the content is published on the WMN website as well.

A focus on the L

But why focus on the lesbian identity, especially when the label ‘queer’ is seen as a catch-all, and often insisted as such? Though Alvarado and Duell don’t mind being identified as queer, the whole group are lesbian first and the mission of the publication is lesbian pride.

WMN is a way of reclaiming ‘lesbian’ in all its diversity and resurgence. All three women agree the identity of lesbian should not get lost as our community expands and diversifies. They have also reclaimed the word ‘dyke.’

Spicer reveals that online trolling has assumed that the publication is anti-queer, which is not the case. Alvarado elaborates: “I think our publication is about the experience of being lesbians in different contexts.” Their approach to the word ‘lesbian’ is expansive and open-ended. When it comes to questioning the limit of the word as a spectrum, they do not have the answer and they don’t wish to.

Despite their different backgrounds and the nuances of identity, Alvarado says “we share a lot of common things about what it is to be a lesbian.” As publisher-editors it is also “humbling” to learn about lesbian experience from other contributors.

Duell emphasizes that they have learned from their contributors as well as made friends with them. The open call is democratic, with no fee to submit. In many ways it is rewarding enough to receive work from people they would otherwise never get to meet, she says. Each issue is then created through sequencing the selected submissions into a narrative based on a topic, with themes emerging and resonating from the juxtaposition and flow of between 20 and 40 contributions.

“The main point of the whole project is lesbian visibility,” says Duell, and to prove that “lesbian identity is not a thing of the past and is not an identification that is inflexible; it is something that is ever-growing and ever-changing, just like us. It is a constant conversation, and a constant dialogue. Every new person who identifies as a lesbian has a new perspective on what it means to be a lesbian, which is how we learn so much from our submissions. There are just so many ways to be a lesbian and how people feel about that.”

Connecting the L and the T

The upcoming issue is themed around the idea of “thresholds” in relation to trans, intersex, non-binary, and two-spirit folks. Alvarado says that the open call yielded a record number of submissions, particularly from younger contributors. “It speaks of the need for people who identify as lesbian but who are non-cis” to be represented, she says. The submissions are varied in their responses to the prompt, spanning identity, the body, love, religion, recognition, and more.

“We really had to think about what we are doing,” says Spicer. For example, “This person identifies as a lesbian and as he/him. It’s just about realizing the world is changing, things are shifting, terms are fluid. In my eyes, in a perfect world, nothing has to go away for something else to exist.”

The future is lesbian

One year in they are still learning as they go.

Spicer says that if they had financial backing WMN would “have a little storefront, and a landline, and lesbian meetings weekly.” Her research at the New York Public Library and the Lesbian Herstory Archives has provoked more than a nostalgia for the decades in which lesbians found each other and communicated through letters, flyers, and zines—it has provoked a desire to answer to the dominance of digital platforms, which are more ephemeral than they may seem. Anyone who has been blocked or suspended knows this and how easily lesbian expression, if only digitally expressed, could disappear overnight.

“We want to have these face-to-face conversations and build community in person, not just on a platform,” says Spicer. As of now, however, you can follow WMN on Instagram here. You can also shop the line of fashion merch here.

The WMN team is considering future pop-ups with readings, exhibitions, and meetings. Spicer invokes the marches and rallies she attends where she sees familiar faces who have been to the WMN launches. That real life community-building is something that happens around a publication, as it did in the heyday of Curve magazine, and will continue to do under the auspices of The Curve Foundation.

“WMN is unique in that we represent specificity at a time when our generation and the generation after is the most fluid we have ever seen in terms of sexuality and gender, and yet we represent specificity and malleability proving that both can exist and that sexuality and gender can be nuanced without losing language and terms we are honored to carry on.”