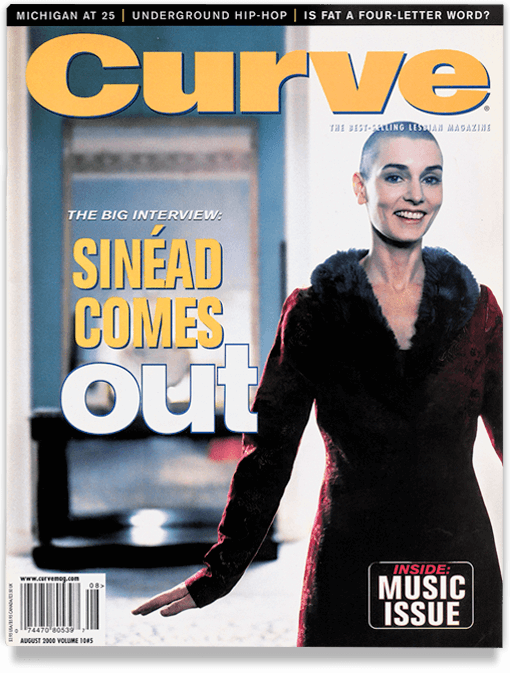

Back in the 1990s and 2000s, in the heyday of Curve as the nation’s most prominent newsstand magazine for lesbians, the pressure to put high profile queer women—and women of interest to lesbians—on the cover was meaningful. It helped sell copies of the magazines in a competitive newsstand environment where Curve found itself side by side with all the other women’s magazines on the shelf. But also, high profile covers were about positive representation, visibility, and giving voice to the women who were standing with our community. We wanted their affirmation, we wanted to pledge allegiance to them, and we loved reading about them. Occasionally, a star would come out in Curve—for example, after years of being in the closet in Nashville, Chely Wright came out in a cover story and was the first country star to come out, period.

But before Chely was Sinéad, and in this the year of the “Nothing Compares 2 U” singer’s death, I wanted to revisit the August 2000 issue of Curve in which O’Connor came out. On the cover. As a lesbian. Or did she?

To get to the bottom of the story I reached out to long-serving former Curve Editor-in-Chief, Diane Anderson-Minshall who personally spoke to the Irish singer.

Merryn Johns

The big interview you did with Sinéad O’Connor became the cover story of the August 2000 issue of Curve. Can you go back to the year 2000 and recall what was happening in lesbian culture at that time?

Diane Anderson-Minshall

Culturally, it was a year after the release of But I’m a Cheerleader, and the year that Ellen DeGeneres and Sharon Stone were in If These Walls Could Talk 2 (an anthology all about lesbiqueer women). Politically, marriage equality was a huge movement. In California (ostensibly one of the most liberal states), voters passed Proposition 22, which declared legal marriage was between one man and one woman. In that state, it took 13 more years before same-sex couples could marry. Vermon got civil unions that year. But there were states outlawing adoption by lesbian couples, and our rights were very much not yet established (In 2000, Arizona repealed their sodomy laws — two years before the federal suit, Lawrence v. Texas ruling mandated that laws that criminalized oral and anal sex in private residences were unconstitutional. Until then, in many states a woman could still be arrested for going down on another woman. I mean, politically we came far in the 1990s, but not that far.) Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell kept military members in the closet; many major religious groups weren’t affirming; Ellen and Mellissa Etheridge were both out but even Rosie O’Donnell was still closeted. Will and Grace seemed like groundbreaking TV.

Merryn Johns

In the August 2000 issue, MichFest turns 25, and I recall queer women in music being incredibly important to our community and the content mix. But at the time we were looking for ‘orthodox’ lesbian role models e.g., kd lang, Melissa Etheridge, more so than queer, trans, bisexual, pansexual—although we were eager for any musicians to come out. What are your thoughts on this and how did it inform your processes?

Diane Anderson-Minshall

Female musicians and women’s music (which should have just been called lesbian music, honestly) were critical to the formation of so many lesbian communities and relationships—seeing open lesbians (even if they called themselves queer) on the stage, singing songs with lyrics that spoke to us directly. I think that had straight women had more access to those songs and musicians, they’d have been bigger fans. I mean, look at the Barbie movie this year: the Indigo Girls song “Closer to Fine” was one of the biggest hits [on the soundtrack].

But yes, you are correct that back then, if a woman came out as bisexual or pansexual, there were a lot of readers who were distrustful of them. Remember, this was the same year that Anne Heche and Ellen DeGeneres had a very public breakup. Anne took the wrath of the lesbian community on her shoulders then and we heard over and over renditions of “I knew she wasn’t really gay” and “She just used Ellen to gain fame and now she’s going back to men.” I think there was often a feeling among some women then that a bisexual/pansexual woman was really queer if they were with another woman, but if they were with a man or dated men, they weren’t really part of the community, they were more suspect. I think back then, barely out of the 1990s, that even femmes were a bit suspect in some folks’ minds. As a queer femme I was aware of my gender presentation and how it impacted other LGBTQ+ folks, and Curve was honestly the most supportive and wonderful place to work, and an amazing experience being one of the longest-serving editor-in-chiefs. But even there, we debated whether someone “looked” queer enough to be on the cover, and whether they were queer enough or just ‘gay for pay.’ I think we have those conversations a lot less now, but honestly I do still feel there’s a sizable group who is dubious of women who come out as bisexual but never have high profile public relationships with other women.

Merryn Johns

How did you land the interview with Sinéad O’Connor and were there any conditions placed on your conversation with her?

Diane Anderson-Minshall

I went around her people and reached her directly, if I recall correctly. I had been trying for years to talk to her and always got a no from her publicist. I can’t recall if she changed her reps in 2000 or if I got her direct number somehow and cold called. I think perhaps that whole decade I had been trying to interview her. But suddenly she was not just willing but eager. It dovetailed with the release of the song “No Man’s Woman,” which was read straightforward as a bit of a coming out:

“I don’t want to be no man’s woman

I’ve other work I want to get done

I haven’t traveled this far to become

No man’s woman”

I know it had more levels, and her usual quest for religious meaning and spirituality, but it sounded like a coming out song so I jumped on it and said, “I’d love to talk about it and your impact on women, etc.”

Merryn Johns

What was your intel about her sexuality prior to the interview?

Diane Anderson-Minshall

For Sinéad, I honestly had not heard many lesbian rumors but I had followed how troubled she was, how much religion had shaped her life, the lyrics to her songs, and the gender presentation she showed the world—and it all looked so queer to me. Younger queer women might not understand this but in 2000 in Ireland, it was still very much a world of restriction for women. No legal abortion, no marriage equality, and overall gender inequality was rampant (as was domestic violence). There’s been a fierce feminist movement there but even today Ireland is a country run mostly by men and that gender inequality is deeply embedded in their systems and hierarchies.

So I thought, is all this mental health stuff merely childhood trauma or a combo of that and PTSD and trying to suppress her own orientation or identity to have her own children (which was very important to her). Let’s see.

Merryn Johns

What were your impressions of Sinéad once you had her on the phone? Any memories about her energy, her mood, her agenda, which some artists have in interviews.

Diane Anderson-Minshall

Her mood was great, she was definitely energetic but so thoughtful. Usually if you do celebrity interviews long enough you start to know if you’re getting canned answers (meaning they’ve said that same thing hundreds of times), PR answers (meaning their reps told them what to say and what not to say in hopes they stay on track), or unexpectedly real off-the-cuff engaged answers to your questions. And Sinead had that. She felt real, she thought long about some of the questions, and gave nuanced answers. I honestly felt like she was much more vulnerable than her public image. She seemed to not have an agenda other than chatting; she didn’t steer me on to any project or arena.

Merryn Johns

Did you have a specific line of questioning planned?

Diane Anderson-Minshall

I go into every interview with specific questions and I pivot during it if something changes. This was a wowzer, because as soon as she came out, I pivoted to talk less about the music and establish a bit more intimacy with her to keep her talking.

Merryn Johns

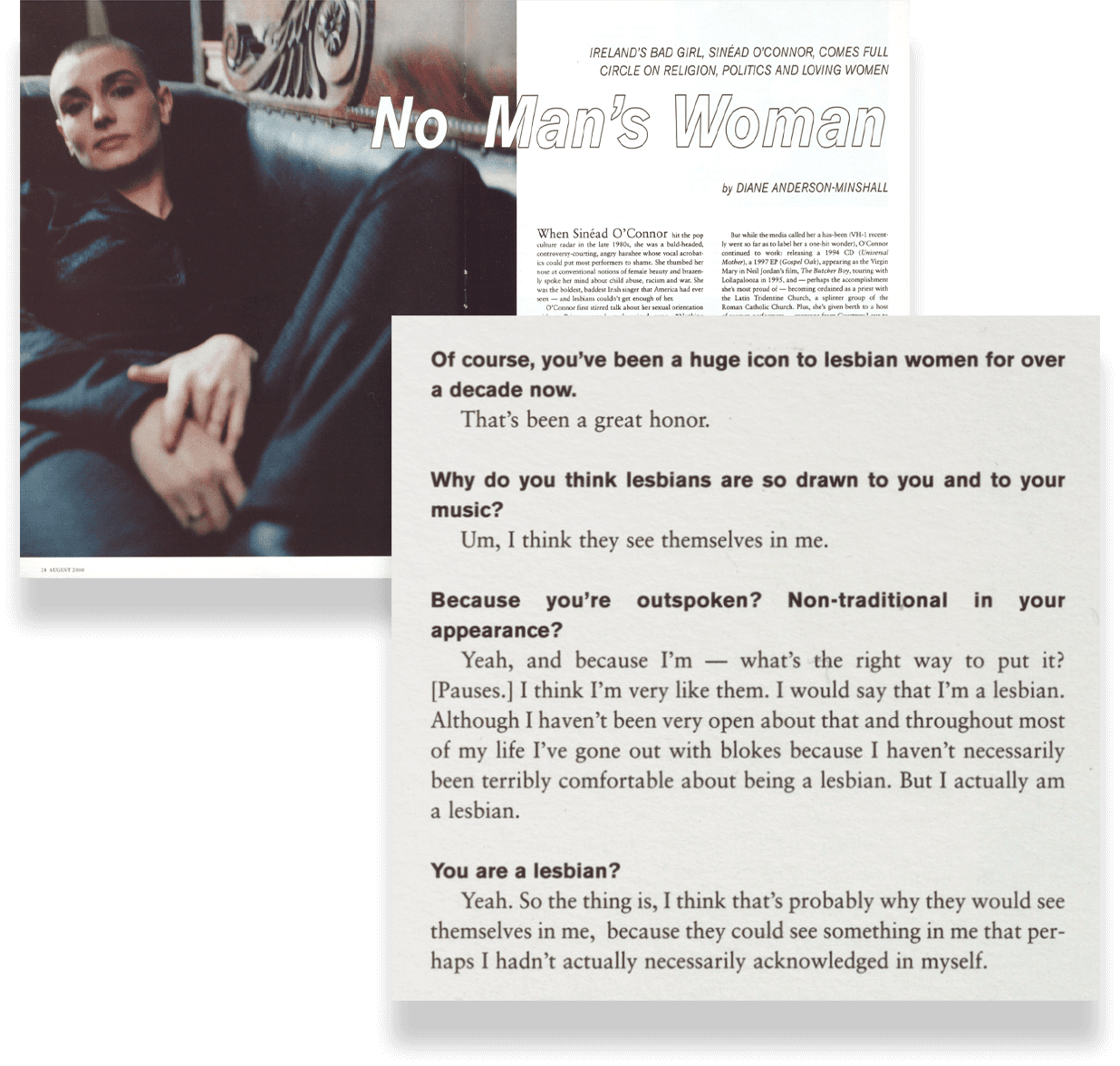

You start the interview by talking about her music and then Catholicism. About nine questions in you segue into lesbian culture and suddenly she comes out! After putting her toe in the water she says, “I actually am a lesbian.” Did you believe her? Did it seem genuine?

Diane Anderson-Minshall

I was dumbfounded but thrilled. In the 1990s, we had so few role models that celebrity coming out interviews were really critical for women around the country to see. In Hollywood, we get all the gossip. But if you’re an ordinary lesbian living in Idaho, playing lesbian softball and watching cable TV in the 1990s, you don’t hear anything about anyone until Curve arrives in your mailbox. Our page of celebrity gossip or updates was among our most popular, in part because it was the only place you could find that info aimed directly at our readers’ interests.

So I went into most interviews then trying to find a way to basically offer a path for someone to come out. If they want to, they could easily. If they didn’t, it never sounded weird or pushy in print. We never wanted to out someone. It was their choice. I just went into every interview hoping they’d make that choice if I said the right thing.

So with Sinéad, when she said it, I was honestly super surprised — and thrilled. If we had Slack back then, our whole office would have started pinging because I always could not believe it. And I verified it to make sure. I know we hung on to the audio cassette of it so we could play that moment in case she later said it wasn’t true. I wanted folks to know we weren’t making this up. We have proof that the woman you thought was queer in 1988, who has only publicly been linked to men, who is now singing about not being any man’s woman, has just said I’m one of them, I’m a lesbian.

Merryn Johns

Given the light of her recent death, and her mental health struggles, do you look back on this interview and reassess it in any way?

Diane Anderson-Minshall

I believe she believed what she said. If I had to identify her today from only the outside looking in, I’d more likely call her bisexual since she’s clearly had relationships with men. But the majority of lesbians have had sex with a man once (or for some, relationships). She had so many mental health struggles, but you know what: most lesbian women who are suppressing their sexuality or trying to become an ex-gay, generally do.

Look, clearly I’m speculating here and could be completely wrong but I think she had so much early childhood trauma and so much “queers are evil” teachings from the Catholic Church for decades, that when you add it to the pressures of being exploited in the music industry, reviled for years after that Saturday Night Live appearance where she tore up the Pope’s photo in protest, inundated in Ireland with the “if you want kids, you need a man” motto, that she tried to fit in while still showing signs of protest that were sometimes severe cries for help (and love). I can’t tell you if she ever had a female relationship, ever loved a woman or had sex with women, but that day what she told me felt 100% authentic. Are you a lesbian if you are single? If you’re asexual? Yes, because your orientation isn’t determined by other people (which is why kids are coming out younger than ever before and many before they’ve ever had sex). So, I think it’s possible for a woman like Sinéad, who wanted kids and wanted to know God as intimately as she could, living in Ireland most of her life, would feel like a lesbian inside even though she had relationships with men (obviously they all failed). And when she did come out she got suspicion and backlash, so she backpedaled.

Merryn Johns

Any other thoughts you’d like to share about this interview, the format of the interview, and your approach to Curve cover stories from that time on?

Diane Anderson-Minshall

I think the kind of interviews we did then were so critical in the 1990s-early 2000s. But today folks come out by announcing it on Instagram. If you think of Raven-Symone, I tried to talk to her for years and only got no. When she came out, she did it on social media. That woman deserves a magazine cover, even if she doesn’t realize it. But I think performers and public figures feel like social media because it is controllable whereas writers and magazine editors are wild cards. I think they’re wrong and it deprives readers of in-depth interviews that let you know someone more intimately.

About Diane Anderson-Minshall

Diane Anderson-Minshall (she/they) is the former Editor-in-Chief of Curve magazine. She is also the former CEO of Pride Media, Editorial Director of Out, The Advocate, Out Traveler, and Plus. She currently consults in digital, print, social media strategy, travel, crime and entertainment writing/podcast/video, branded content creation, top-line editing, and DEI/LGBTQ+ projects.

Diane is queer, Indigenous, and is the author of four novels and a memoir, Queerly Beloved: A Love Across Genders. She is the winner of numerous awards from GLAAD, NLGJA, WPA, and was named to Folio’s Top Women in Media list.