PHOTOS COURTESY OF AMAZON MGM STUDIOS

Last year wasn’t a particularly strong year for ‘lesbian cinema,’ and according to The Hollywood Reporter, films directed by women dropped to a seven-year low.

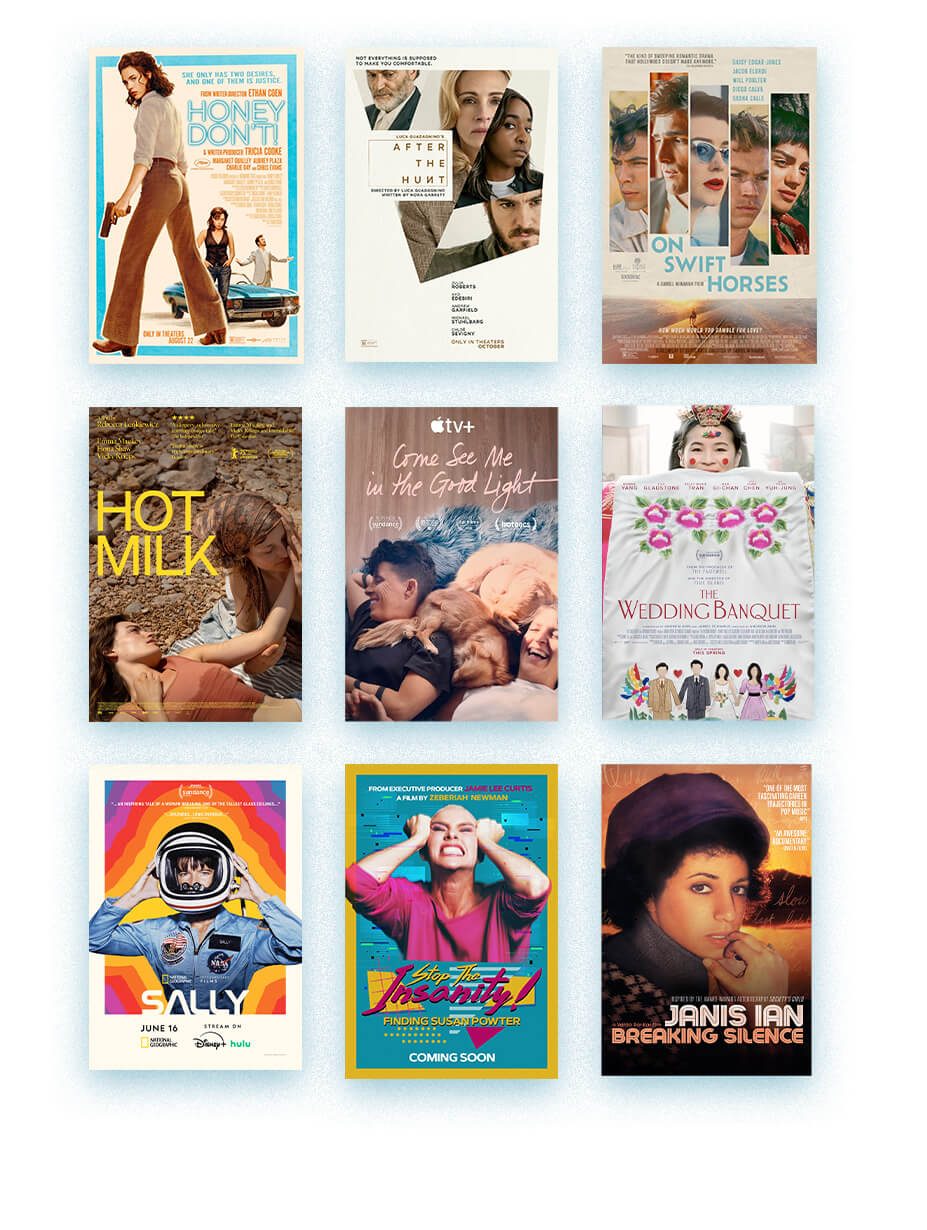

In a handful of mainstream feature films, female queerness was present but sidelined, unaddressed, or used for thematic novelty: After the Hunt (a queer supporting character played by Ayo Edebiri); Honey Don’t! (Margaret Qually and Aubrey Plaza in a comedy-thriller co-directed by Tricia Cooke); On Swift Horses (1950s housewife Daisy Edgar-Jones experiments with queer Sasha Calle).

In a couple of films, relationships between female leads are pivotal: Hot Milk (Emma Mackey, Vicky Krieps, and lesbian icon Fiona Shaw, directed by Rebecca Lenkiewicz in a bisexual coming-of-age story); The Wedding Banquet (Lily Gladstone and Kelly Marie Tran agree to a green card marriage with a gay man in exchange for IVF treatment).

In documentary-land, real-life queer women fared better with Sally (directed by Cristina Costantini about the life of astronaut Sally Ride and her partner Tam O’Shaughnessy); Janis Ian: Breaking the Silence (about the LGBTQ music icon, directed by Varda Bar-Kar); Stop the Insanity: Finding Susan Powter (the former fitness guru comes out as a “total lesbian”); and Come See Me in the Good Light (poet/activist Andrea Gibson navigates incurable cancer with partner Megan Falley).

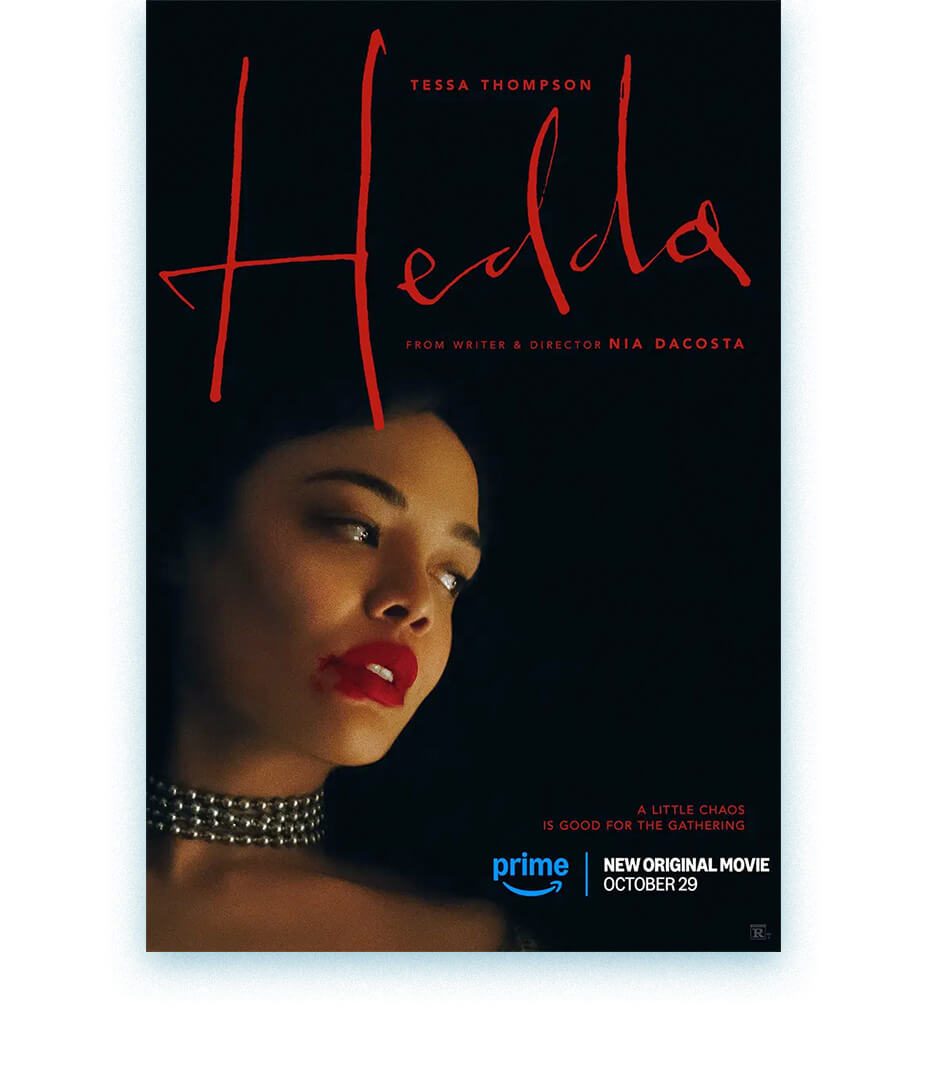

Returning to the world of fictional feature films, there was one mainstream offering that stood out to me for several reasons: Not only is it helmed by women (the writer-director, leads, and three producers), but it also confronts the issue of telling queer cinematic stories within a patriarchy: Hedda, now on Amazon Prime Video.

In the world of narrative, the patriarchy trumpets male protagonists—even when they are errant failures (Marty Supreme, anyone?). Arguably, this all started with Hamlet. Does such a text exist for women? Unofficially, in the form of Hedda Gabler, the 1890 play by Norwegian Henrik Ibsen. Required reading for drama students, the title role attracts actresses of gravitas: Eleonora Duse, Alla Nazimova, Eva Le Gallienne (those last two, lesbians). Ingrid Bergman, Claire Bloom, Glenda Jackson, Maggie Smith, Diana Rigg, Peggy Ashcroft, Judy Davis, Janet Suzman, Jane Fonda, Annette Bening, Fiona Shaw, Ruth Wilson, Harriet Walter, Isabelle Huppert, Cate Blanchett, Rosamund Pike, Mary-Louise Parker, and Nina Hoss have all played Hedda.

Hoss, a German actress known to U.S. audiences for playing Cate Blanchett’s wife in Tár, revisited the text under its queer new revision. Hedda (2025, Prime Video) stars Tessa Thompson in the title role, written and directed by Nia DaCosta. Ibsen created the character to explore what happens when an intelligent, ambitious woman is trapped in a restrictive, male-dominated society. DaCosta maps this question onto a queer woman of color and ups the ante with a lesbian love triangle involving Hedda, Eileen (formerly male character Ejlert Lovborg), and Thea Elvsted, Hedda’s old school friend and now Eileen’s submissive lover (played by Imogen Poots).

DaCosta and Thompson’s Hedda is, like Ibsen’s, a critique of patriarchal oppression and a frightening portrait of the resulting pathology. But it goes beyond that, with the heart of the matter being the relationship between Hedda and Eileen, which has become competitive and destructive.

While Ibsen wrote the play at the beginning of the suffrage movement and the rise of the ‘New Woman,’ DaCosta revises the story in a post-feminist climate in which the movement is widely considered to have failed either on its own terms or because society has failed to implement its goals.

Hedda does not possess freedom, power, or autonomy, but she has inherited her father’s pistols and has become mistress of her husband, George Tesman’s, house, both of which she misuses; she is not in control of her life’s story, so she steals her lover’s manuscript.

The idea of misdirected agency in a strong-willed female protagonist is queer-coded: LGBTQ individuals, operating within a heteronormative society, must often find alternative ways to express themselves and shape their lives. (In an interesting side note, lesbian playwright María Irene Fornés wrote The Summer in Gossensass, a 1989 meta-theatrical play about suffragists and lovers Elizabeth Robins and Marion Lea trying to stage the first English-language production of Hedda Gabler in 1891 amid opposition and censorship.)

PHOTO: NIA DACOSTA DIRECTING TESSA THOMPSON

In a sit-down with Curve and select media, Nia DaCosta revealed she first read Hedda Gabler while studying for her Master’s degree at London’s Royal Central School of Speech and Drama. She was struck by Ibsen’s investment in “complicated, interesting, confrontational women,” and by the sexually subversive subtext. She felt previous productions had skipped over the hidden themes in the play.

“I started to kind of fill in my own little pieces,” she says, and made some “big changes.”

While Tessa Thompson isn’t the first Black woman to play Hedda (CCH Pounder starred in a 1995 San Diego production), she is the only LGBTQ Black woman to do so under the direction of another Black woman in a queer creative dialogue.

When DaCosta changed the sex of Hedda’s former lover from male to female, “the whole world becomes so much more dangerous for all the characters,” says Hoss.

Eileen Lovborg, a brilliant but alcoholic sociologist and a rival to Hedda’s husband for gaining tenure, becomes a powerful figure in Hoss’s hands: a female sexologist. “Just in the fact that she’s a woman, it is everything,” says Hoss. “And I found that mesmerizing and very fascinating and exciting.”

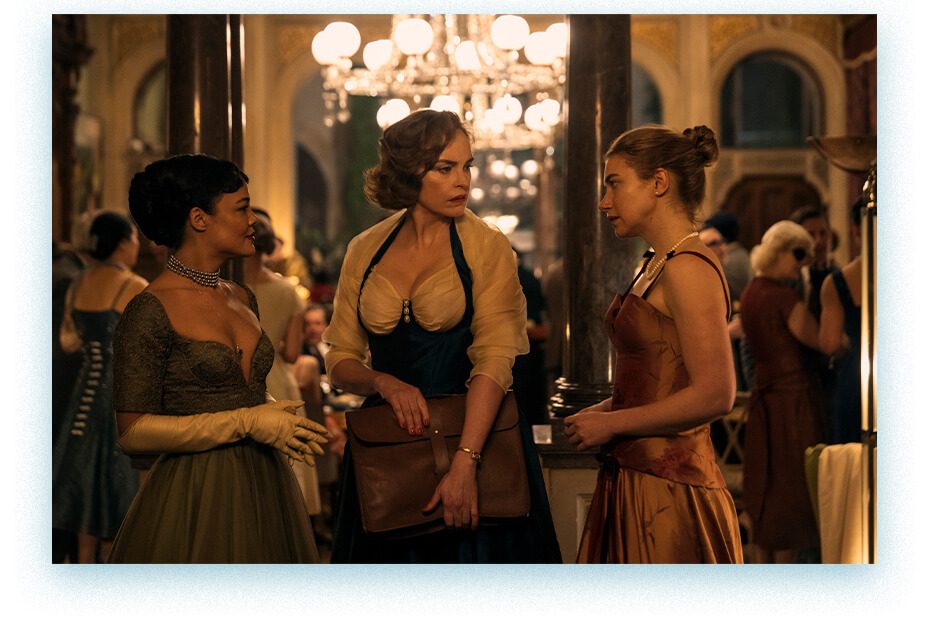

(L-R): TESSA THOMPSON, NINA HOSS, IMOGEN POOTS

For Hoss, the film’s main theme is finding freedom and gaining control within society’s expectations. “Are you really the person that you want to be? Are you really leading the life that you want to live? Or do you live it because you think others expect certain things from you? So, are you then in control of your life? Do you want to be in control of your life, or do you want to have adventures? Do you want to create chaos to feel yourself?” asks Hoss. She thinks that the characters “want to provoke the world to see what their place is in it.”

Thompson says that DaCosta’s big changes mean that Hedda has a shot at “loving who she wants to love” and that Eileen is “a really challenging foil for Hedda. And then I think the question becomes, How much are we trapped by our own limiting thoughts and the limitations that we put on ourselves? And the ways in which we suppress and repress our own personal power and personhood. I think that’s something that makes the piece have relevance, particularly in this time. We like to think that we live in times that are very free, and to a certain extent, that’s true. And in other ways, I think we as humans sometimes feel trapped by the times that we’re in, by the times that came before us.”

DANCING TO ‘IT’S OH SO QUIET’

Thompson’s Hedda is clearly aching to unleash herself (giving crisp orders to servants in her “big swing” at an upper-crust British accent, dancing to Björk/Betty Hutton’s ‘It’s Oh So Quiet’). DaCosta gives her full rein.

“For me, the kind of riot or chaos in Hedda’s mind begins when she first hears Eileen’s name when she’s in the river at the top of the movie,” she says.

In this scene, Hedda is submerging herself in what could either be a suicide attempt or a baptism, but stops when she is summoned to the telephone by a call from ex-lover Eileen, whom she has invited to her huge, Gatsby-esque housewarming party. She is coming.

Surely the moment when Hedda first locks eyes with Eileen as she arrives at the party is the best lesbian meet-cute of 2025, with DaCosta summoning her full powers as director.

THE DOUBLE DOLLY MEET-CUTE

“I always knew we had to get [Hedda] across the room in a way that felt magical,” explains DaCosta. “The way I wrote it was: everyone stops, she walks across the room, her footsteps echo, but then I was like, we need more, we need to push it further, so Sean Bobbitt (cinematographer) and I did the double dolly and also used the cine-fade to shift the depth of field as the shot was happening.”

In acting that scene, Thompson adds, “I knew that their history and magnetism needed to be expressed, this feeling of when someone enters a room, and they mutate time, they slow it down or speed it up.… In moments, I couldn’t really see Nina. I could just feel her presence across the room. I got to do the whole double dolly thing, but Nina just comes in and stands in that dress, and she looks like she can completely change time and space, and that’s just her.”

Hoss says, “I saw Tessa on the dolly floating towards me… this is such a gift we’re being given, to have this moment captured like this and to know that this is a moment of pause, but also it’s the beginning of something else. Now the whole evening, something shifts.”

And what shifts, of course, is that this story is clearly not going to be about women talking about men, but “about women,” says DaCosta.

Now set in the 1950s, it’s still a time of “great pretending,” says Thompson. These characters are awash in cocktails, party dresses, chandeliers, games, and mazes—compensation for still being trapped.

Hedda is “a woman who feels a tremendous amount of pain, and also, when she hurts others, it costs her something emotionally,” says Thompson, “and that was the only way I understood how to play her. If there’s a sense of vulnerability, that’s where it comes from because for me it felt kind of painful, and then also painful to have to perform pleasure.”

In line for academic tenure, Eileen hits the glass ceiling when she joins the men in the study to pitch her new book, and she is ridiculed and harassed. Hoss described it as a “painfully relatable” moment.

“Eileen walking into that room of men, that’s incredibly brave,” says DaCosta. “And for Hedda, she’s in so much pain, and for her to just get out of bed every day, that’s a kind of bravery as well. These are all women who are toeing that line and discovering what that means for them, even if they’re not conscious of that journey.”

“I didn’t set out to make a queer film,” says DaCosta. “But of course, when I changed Ejlert to Eileen, I was like, Oh, okay, now we have a queer hero at the center of the story. And that texturizes everything that they go through.”

I don’t want to spoil the ending, but the biggest and queerest revision is possibly there.

“The only thing I really thought of that I wanted to be careful of was the Kill Your Gays trope,” reveals DaCosta. “That was something where I was like, Oh, I don’t want to lean into that. There’s also the ‘sad lesbians in the past’ thing, but I was like, Too late. It’s too bad. That’s what’s happening.”

As for me, I’m not opposed to ‘sad lesbians in the past’—if you do something new with them now.

After Hedda has devastated Eileen and Thea, and just about everyone else, she walks into the river with rocks in her pockets. When she hears Eileen is still alive, she stops. And smiles.

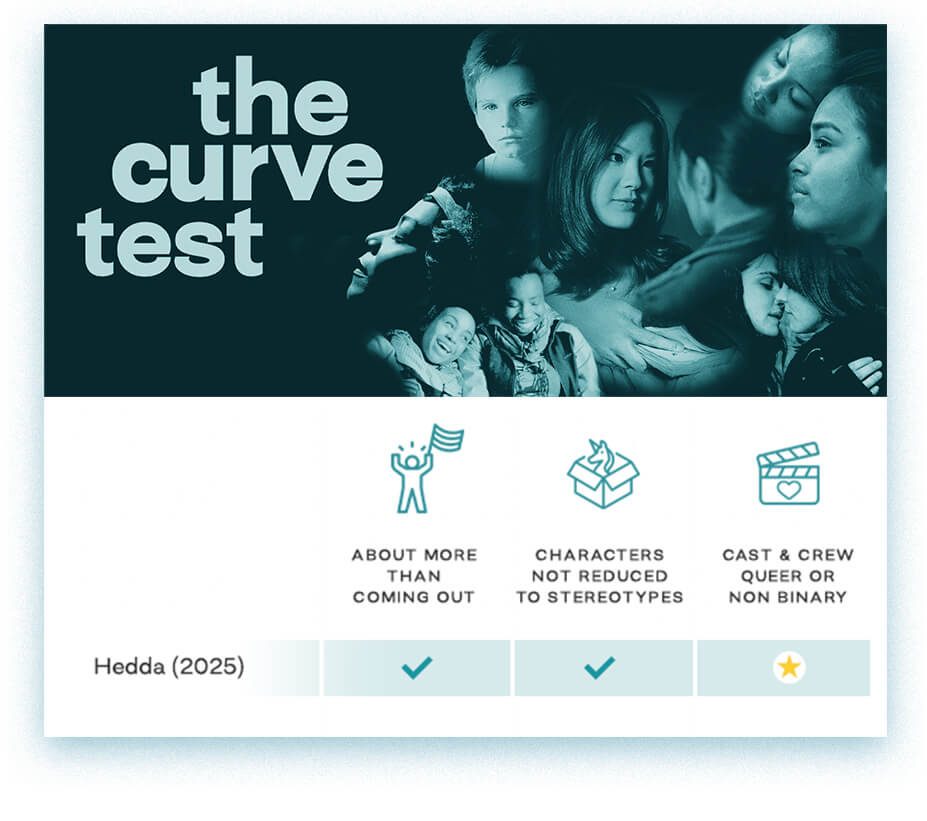

Visit The Curve Test here.