PHOTO COURTESY OF CRITERION CHANNEL

It was the first lesbian movie to have a relationship that didn’t culminate in abuse (The Killing of Sister George), suicide (The Children’s Hour), murder (Les Diaboliques, Windows), death (The Fox), or a bisexual triangle (Les Biches, The Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant, Personal Best, Lianna).

Even though the repressive Hays Code prohibiting “any inference of sex perversion” on screen was repealed in 1968, U.S. film culture had not caught up. Artist-activist Barbara Hammer’s short film Dyketactics was released in 1974 and premiered as a student film at San Francisco State University. But the first feature-length film about non-tragic lesbians in love to screen in cineplexes is Desert Hearts, directed by Donna Deitch and released in 1986.

In post-war America, until recently, fewer than .2% of American films were directed by women, and like many lesbians over a certain age, Deitch had grown up with and studied movies that pathologized and condemned her or anyone like her. Studying at UC Berkeley, initially painting and art history, she shifted to photography and then film, shooting 8mm and Super 8 during the heart of the anti-war and free speech movements.

“That’s when I really became politicized, and I was making short films coming out of the inspiration of my own politicization,” she tells me. “And so, a lot of feminists back in the so-called ‘second wave’ came out of the civil rights and anti-war movement. That was the beginning of many of our political lives. I really think no one expressed that better than Robin Morgan, who was the first person to ever say ‘the personal is political.’ That was certainly true for me, so I segued from the anti-war movement into the feminist movement, and within the feminist movement, I became a lesbian.”

Desert Hearts would be the result of “living out the personal is political.” Deitch was driven by the desire to tell the story of the identity she lived. “I started out by thinking what it wouldn’t be. It would not be a film that ended in a suicide or a bisexual triangle. It had to be a lesbian love story,” she says. “It had to be hot, very hot, because that’s at the core of it; it had to be funny; and it had to be authentic. It wasn’t as though I was trying to make the first of anything at all. I just made the film I wanted to see.”

Deitch was going for “intentionality, focus, and timing,” her recipe for getting anything done. While writing the original script, a friend gave her Jane Rule’s novel Desert of the Heart.

“I read it seven times in a row. I fell into the world of this story. It took place in the midst of a 1950’s hetero ritual: divorce Reno style. It really had the elements I wanted in the story, and I needed to interpret this in my own way. It had a very strong metaphor: If you don’t play, you can’t win.” (That mantra would later appear in the film, with Deitch in a cameo as a gambler who delivers the line to Vivian Bell). It was a radical premise for lesbians in a culture that had previously stated, If you play, you will be punished.

“I began to picture it,” says Deitch.

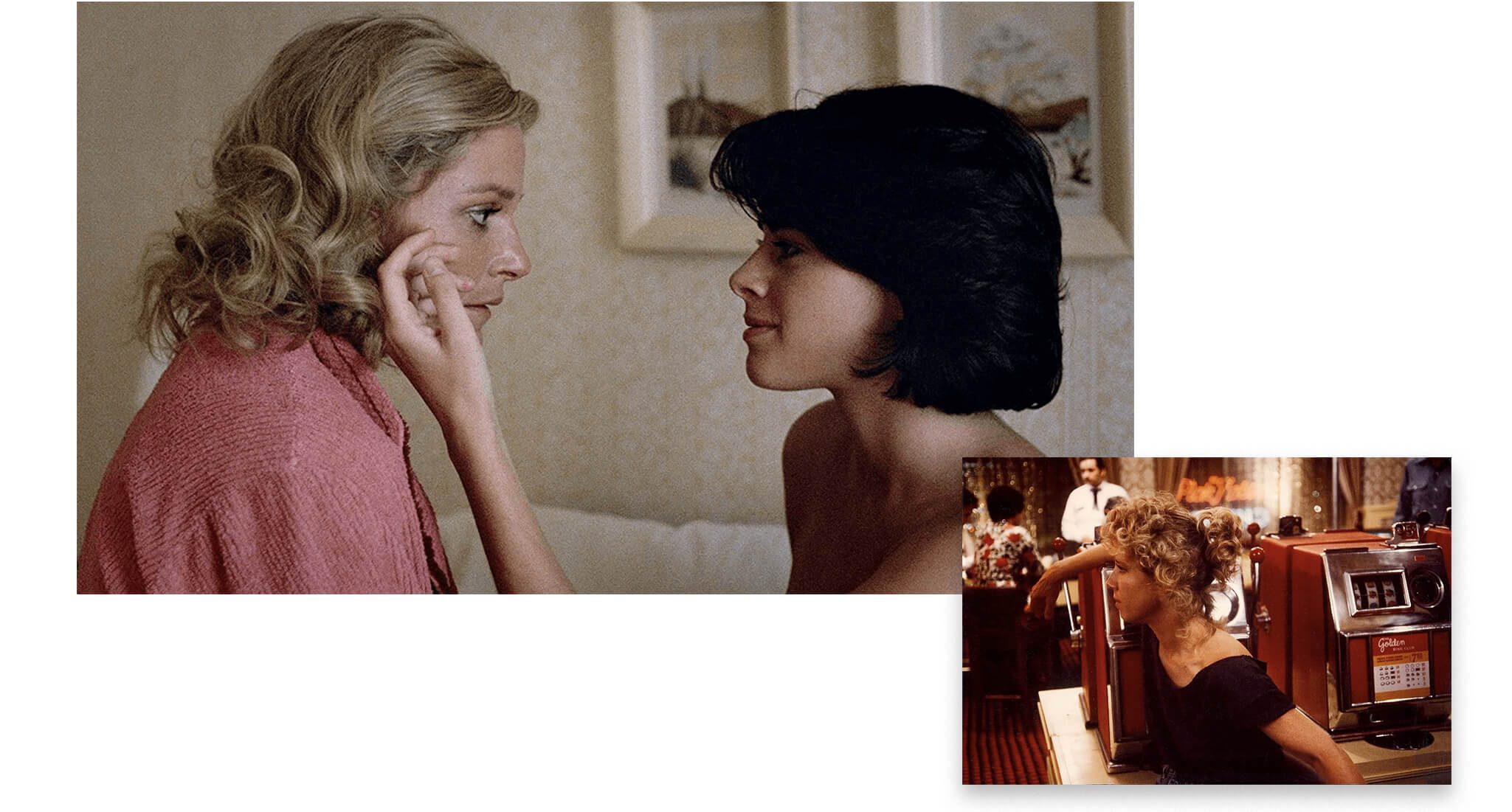

HELEN SHAVER AND PATRICIA CHARBONNEAU IN THE LOVE SCENE; DIRECTOR DONNA DEITCH ON SET

POWERED BY WOMEN

Deitch adapted the novel into a screenplay and went about raising the budget. Once she’d written the script, she attended two Hollywood studio meetings and was horrified by the outcome. In both meetings, they said the two women had to break up in the end. She’d have to find the money herself.

She didn’t know anyone who might invest in the project, so she started asking everyone she knew if they did and compiled a list of mostly women and a few feminist men. She got her script to enough people for cocktail parties from NYC to San Francisco, L.A. to Chicago. She needed a printed invitation. So Deitch set out to meet Gloria Steinem. She hoped America’s most-quoted, famous feminist would get behind the project. In 1980, Deitch secured a meeting, gave Steinem the script, which she loved, and when Steinem asked to see a film she’d made, Deitch screened her 1975 UCLA graduate thesis film Woman to Woman: A Documentary about Hookers, Housewives, and Other Mothers. “Then came the famous four words from Gloria: How Can I Help?”

Deitch wanted Steinem to endorse her fundraising parties. Steinem agreed. “I always say to Gloria, You’re my first producer. She’s been an inspiration to everyone.” Deitch also convinced Lily Tomlin and Stockard Channing to sign on, then she went to a hypnotist to overcome her fear of public speaking. Over the next two-and-a-half years, Deitch raised $1 million at $15,000 per share from women’s gatherings and backers’ parties coast to coast.

THE VISION OF DESERT HEARTS

Deitch knew that to get the script to full potential, she needed a rewrite “by a collaborative spirit, a master of dialogue, an original thinker, a writer who made me laugh, and was at least 100 times better than me,” and that was Natalie Cooper. “I told Natalie I’d be flying up to Oakland every weekend so she could hand me 10 pages to read and discuss over some fabulous meals we’d have together. But first, I would take her to Reno to see all the locations I’d chosen from the ranch house to the casino, from the train station to the cars they would each drive. This was the beginning of a friendship through which I got some of the best laughs and advice of my life. Natalie went to the other side in 2004.”

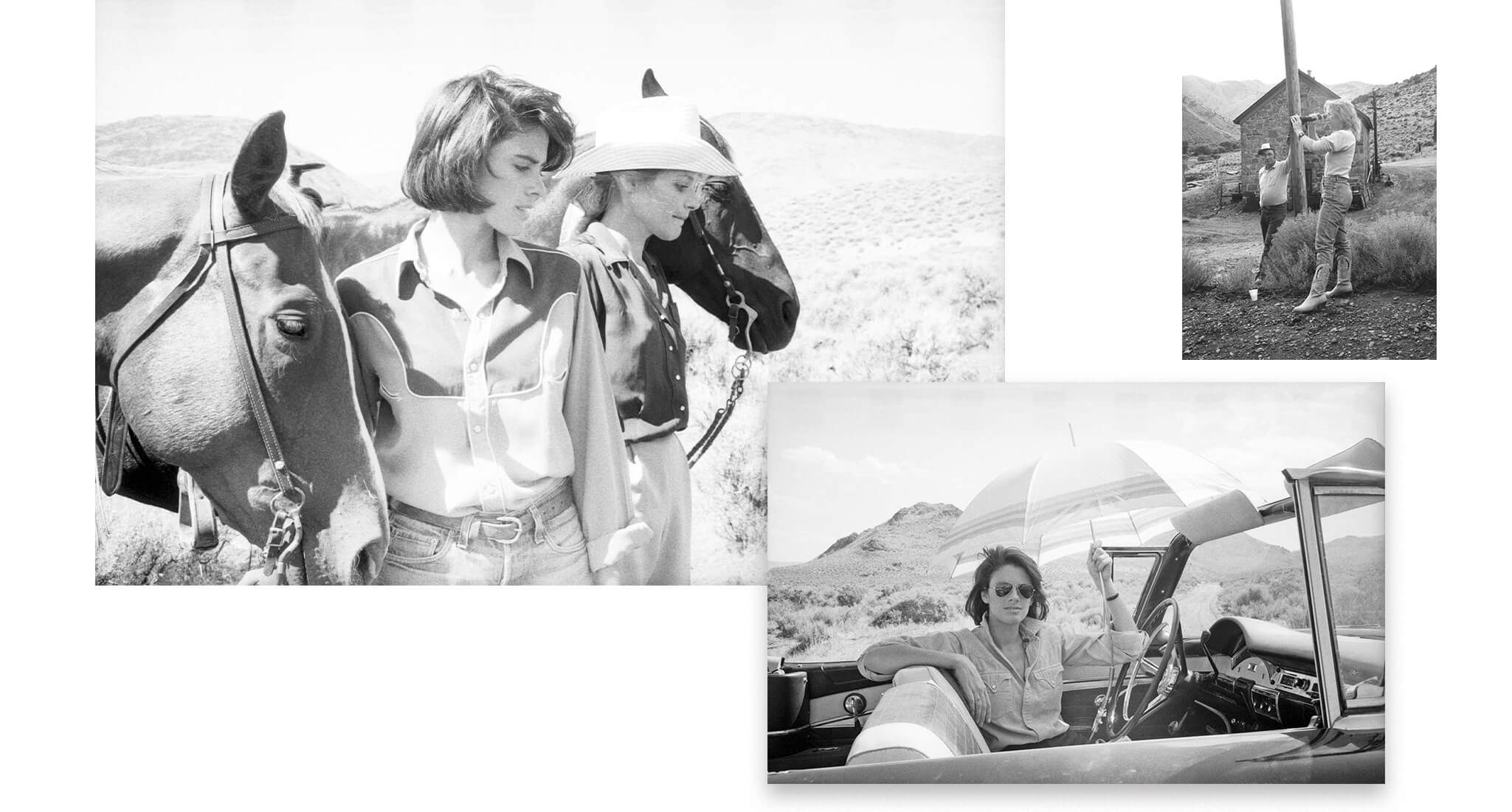

Set in the 1950s, in a reimagined West, Desert Hearts could afford to “make a more radical statement than about the time we’re in,” says Deitch, who drew on one of her favorite movies, The Misfits (1961)—a proto-feminist film about Marilyn Monroe’s character, who comes to Reno for a divorce and challenges masculine stereotypes.

“As a child, I had always loved cowboys and horses,” says Deitch. “I saw that I could make this into a lesbian version of John Huston’s The Misfits—in color!”

In the novel Desert of the Heart, the primary setting is a rooming house in Reno. Deitch switched that to a dude ranch, surrounded by nature and horses—lesbians in a cowboy’s world, the expanse of the West a metaphor for coming-out: the final, long-overdue emergence of the American lesbian on screen.

Visually, it was brought to life by the yet-to-become Oscar-winning cinematographer Robert Elswit (There Will Be Blood) and the four-time Oscar-nominated production designer Jeannine Oppewall (L.A. Confidential; Pleasantville).

“The quality of all the individuals that Donna had attracted was so high,” says Helen Shaver, who plays Vivian Bell. “It was just an extraordinary group of people. And we were all there to make this movie because we loved it.”

CHARBONNEAU, SHAVER, AND DEITCH ON LOCATION IN NEVADA

‘REAL CHEMISTRY’

“I knew she was Cay Rivvers,” Deitch tells me, recalling the moment she first saw an 8 x 10 of New York theater actor Patricia Charbonneau. “She came in the next day, she read the script, and I knew she was the one, without any doubt.”

Charbonneau confirms that her headshot and résumé somehow landed in that casting office, but the defining moment was a meeting where she and Deitch just sat and talked.

“Donna said, How do you feel about playing a lesbian, and how comfortable are you taking your clothes off with another woman and making love with her? I said, Well, I’m the last of five sisters, and I had just come off doing a play called My Sister in This House (based on Jean Genet’s The Maids). I looked at [Desert Hearts] as a love story, as a kind of classic Hollywood love story.”

Deitch flew Charbonneau out to L.A. to read with three possible Vivian Bell candidates. When she read with Helen Shaver, “you couldn’t help but see there was real chemistry between them, and it was obvious in the room, there was no conversation or disagreement,” says Deitch.

What does chemistry between straight women look like, I wonder. “It looks like the real thing,” says Deitch.

Shaver had been sent the script and had a “remarkable” experience with it. Even though it was 1984, she had been warned by her own agent, a gay man, not to do it. “No, no, no,” he said. “They’re all going to think you’re gay.” Shaver’s response was “So?” When she opened the script and read the description of Vivian getting off the train, she knew, viscerally, that she was going to do the film. When she read with Charbonneau, she recalls “the energy was flowing.”

A Canadian transplant in L.A., Shaver, then 33, was a naturally intellectual, sensitive, relatively established actress. As a child, she’d suffered years of illness and retreated into her imagination. She was perfect for the role of the smart but repressed professor longing to live.

A plucky “East Coast kid” and a student of the legendary acting teacher Sanford Meisner, Charbonneau, 25, had never done a film, but took a job at a casino so she would be convincing as the free-spirited, wild-card “change girl” who sets out to seduce the professor and change her heart.

ON LOCATION

Desert Hearts was filmed over 31 days in and around Reno, Nevada. Everyone has retained vivid memories. Just thinking about it, Charbonneau says she can smell the desert air and the chaparral. Both she and Shaver count it as the source of many blessings in their lives.

Cast and crew stayed in a funky 1950s motel with a swimming pool. The atmosphere was like “a little theater troupe off somewhere making a play in some little town,” says Deitch.

“There was a lot of sex going on out there, every gender combination that exists,” she reveals. “Unfortunately, none of it involved me because I was way too busy working. But it was quite a lot of fun. And those who had been on many more film sets, they were always saying, ‘It’s never going to be like this again.’ I’d say, What are you talking about? ‘You’ll see.’ It was a very personal experience for everybody.”

Personal, indeed. While filming, Shaver met her future husband; Charbonneau revealed she was pregnant; Deitch met her soon to become best friend and muse for her documentary Angel On My Shoulder, Gwen Welles; and Audra Lindley was the only cast member to receive a bed change every day by housekeeping because the staff recognized her as Mrs. Roper from Three’s Company. (So invested in her role as Frances Parker, Lindley would buy a share in the picture so Deitch could finish post-production.)

“Audra—I mean, oh my God. To me, she’s stellar. I can’t tell you enough about what an incredible experience it was to work with her,” Charbonneau enthuses about the veteran actress who mentored her. “It was so great to be surrounded by so many incredible, astonishingly beautiful, and amazingly talented women. And I was so excited that it was a woman directing it.”

A WOMAN DIRECTOR

On her first day on set, Shaver found that Deitch had sent her flowers and a note. “In that letter, among other things, she said ‘I want all of you, Helen, I want all your experience, I want all of you for this project, that’s what it needs, and we have little time, so if we have a disagreement, we must solve it quickly and move on…’.”

Deitch confirms this. “What’s at the heart of this film is a love scene that’s never been seen in film, and I need to know you are committed to this story, to this love scene, which requires you take all your clothes off and do the scene full out.”

Deitch reveals agents were telling their clients, “‘Don’t even come near this film, you’re never going to work again if you do this.’ So I really had to know there wasn’t even a hint of that restraint or attitude because I had to make this movie, and I knew what I wanted this to be, and I couldn’t have anything that wasn’t that. All the actors were fully supportive of everything about this movie; they loved the script and the process. And that these two women, these two actors, would commit themselves to this project 100 percent was my absolute favorite thing I’ve ever experienced as a director in my life.”

Working with Deitch inspired Shaver to pursue her own career as a director (five movies and many TV series). “You’ve got to see it to be it, you know, there’s truth in that,” she says.

Deitch would go on to sit on many ‘women director’ panels and would always advise, “When you’re looking to hire a director OR a gynecologist, you’re really better off hiring a woman. It just makes sense!”

CHARBONNEAU, SHAVER, AND DEITCH ON LOCATION

THE MEET-CUTE

In the first-ever “hot, very hot lesbian love story for the big screen,” Deitch knew the way the protagonists met was key in establishing who they are.

In the book, Cay and Vivian meet in the rooming house parlour and shake hands. Deitch wasn’t having this. “When they meet, it cannot be in the house. It’s gotta be out there somewhere. They have to meet as no two characters have ever met! Cay has to be doing something that tells us who she is! What’s it going to be? Figure it out!” Deitch told screenwriter Natalie Cooper. A couple of days later, the scene was written.

“I was so excited I could hardly stand it. Who drives backwards at 60 miles an hour?” says Deitch. Cay Rivvers, that’s who.

“What an entrance for an actor to have for their first time on film. I mean, you can’t beat it,” says Charbonneau. She kept a bucket on the seat beside her so she could throw up between takes, nauseous from morning sickness and motion, both cars facing different directions on flatbed trucks driven by Teamsters.

“That was wild,” says Deitch. And, of course, the best lesbian meet-cute in cinema history required a world-beating lesbian love scene.

THE LOVE SCENE

Absent from the book, Deitch had the intention of making the greatest lesbian love scene of all time and insisted, “It has to be hot, it has to be authentic, it has to be real, and it has to be funny.”

‘I’m not taking my robe off,’ says Vivian. ‘Everybody draws the line somewhere,’ concedes Cay.

Deitch watched dozens of love scenes to figure out what didn’t work and what was missing. She wanted a three-act structure for the scene and “an emotional base that would support the physical, sexual part of it.” She also wanted to implement the lesbian gaze so that “it’s not over when you think it’s over.”

“The scene is long and intense, and it remains that way for us, all these years later,” Deitch says. She didn’t let anyone else into the room when the camera was rolling except the actors, the cinematographer, the sound person, and the focus puller. As for Deitch, “I took on a second job of ‘spritzer’ to reduce people in the room. It too was a lovely job to have.” She didn’t change the camera setup, relight, and get an opposing angle, or add a musical score. “I heard the sound of church bells coming from a nearby church. At that moment, I knew those bells and a few more were all I needed.” These choices contribute to the intensity and the feeling of being in bed with the characters throughout. It’s not just a sex scene. It’s an arc. Vivian goes from pushing Cay away to wanting more.

Shaver had decided that the Columbia professor who lived entirely in her brain, wooden below the heart, had probably never had an orgasm before. According to her memory, the scene wasn’t choreographed, but she played it like a piece of music. She recalls letting the energy rise up in her and feeling a “whole quiver.” She didn’t discuss the scene much with Charbonneau, but says, “Patricia and I, we loved each other. We took care of each other as lovers, too. And so you were also witnessing two people who were with each other in the moment, experiencing the journey which you know takes hours, you should seem like that, right?”

“That was an entire day of shooting,” says Charbonneau. “I don’t even remember taking lunch, taking a break, I don’t remember that at all. People were outside if we needed anything, but nobody was in the room. It was just us. We obviously had to feel really comfortable with each other, and we did, because we didn’t do the scene until the end of shooting. We kind of shot it in sequence, we did the outside the door first, then coming in the room, then me leaning on the dresser…”

Watch the scene to see how Deitch orchestrated something that had never been seen on celluloid before: two actors with no language for lesbian lovemaking, creating it right before your eyes.

“We trusted Donna,” says Shaver.

Later, under pressure from the distributor to cut the scene for length, Deitch flatly refused.

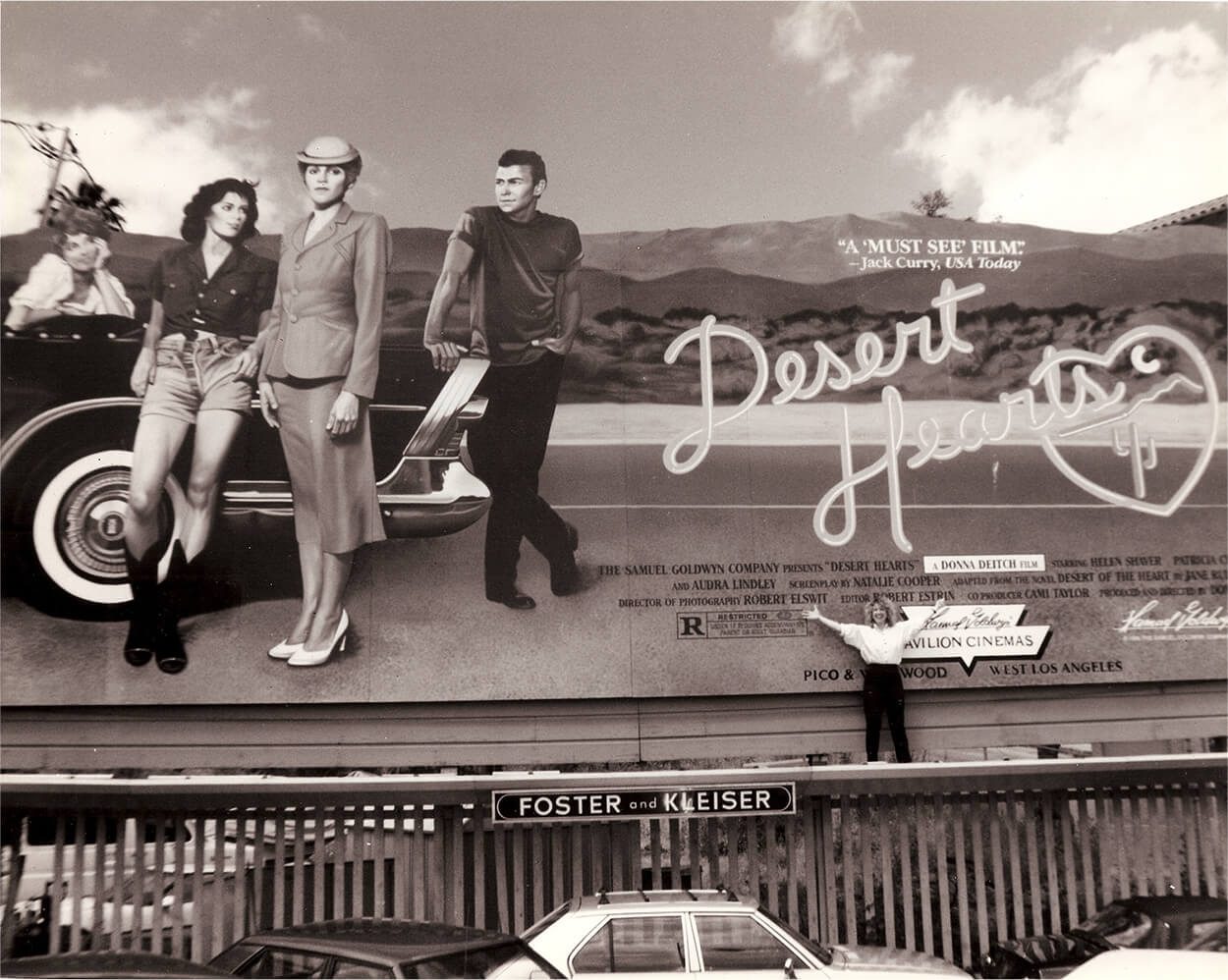

DIRECTOR DONNA DEITCH CLIMBS ONTO THE BILLBOARD FOR DESERT HEARTS, ON SUNSET STRIP, L.A.

THE REACTION

Charbonneau recalls, “I definitely felt that it was very special, very unique, and I knew it was gonna be ahead of its time, risky, and I wasn’t sure if anybody would ever see it—you know, maybe in a few art houses or something like that.”

She recalls Deitch sending her a photo of a billboard for the movie on Sunset Boulevard, and later seeing the cowboy motif popping up everywhere in women’s fashion and lesbian culture. Charbonneau’s Cay Rivvers is arguably the Shane McCutcheon (The L Word) of her day.

“It was sort of like Zen mind, beginner’s mind,” says Deitch. “It was pure. But when it came out, people were shocked.”

Desert Hearts was sold to the Samuel Goldwyn company and had its NYC premiere at Cinema 2 in the Spring of 1986. Goldwyn told Deitch to go to the New York Times building at 11 pm on the night before it opened to get the next day’s paper, read the review, and call him.

“It was the worst review ever,” says Deitch. “Back in that day, any review that was bad from Vincent Canby, especially any indie film without stars, you were dead, you were gone, you were over. It was very scary and upsetting.”

But she had a plan, which can be traced to her politicization on the steps of Sproul Plaza. She had distributed Desert Hearts leaflets announcing the opening to people standing in line for movies for a solid week, telling them she was the director and wanted them to see her film opening the following week. On opening weekend, all these people started showing up to see the film. Then, she would go to the front of the theater before each screening and ask them to tell all their friends about the film, and to come opening weekend because “Mr. Canby just didn’t get it.”

“What happened is that the opening weekend came within seven tickets of the box office record that was set by Rocky. Desert Hearts became what they called a ‘Canby buster’—an independent film that survived a terrible Canby review.”

There were rave reviews from Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert, as well as from all the main mastheads and industry papers. Desert Hearts won numerous awards, including the Special Jury Prize at Sundance and Best Actress for Helen Shaver at the Locarno International Film Festival. Charbonneau was, aptly, nominated for an Independent Spirit Award.

The festival premiere at Telluride on Labor Day weekend was a big hit. Deitch and the actors went from “complete anonymity to center stage 60 minutes after the movie screened,” she says. At the end of the four-day festival, being mobbed by fans, Shaver remarked, “Well, I know that I’m never going to be homeless in my life because there’s going to be some lesbian somewhere who’s going to take me in.”

“I was glad that it was going so mainstream, that it wasn’t just gonna be hidden,” says Charbonneau. “I was so happy about that, and then, of course, the response I did get was quite amazing—letters from women literally all over the world, thanking me, grateful that they could see something like this.”

Years later, while directing a TV series in Ireland, Shaver heard about a coveted, illicit VHS copy of Desert Hearts (it was suppressed there), circulating among women.

Meanwhile, Deitch’s life was forever changed when Oprah Winfrey hired her to direct The Women of Brewster Place (1988), a dramatic miniseries starring top Black actors of the time and featuring a lesbian subplot.

Deitch went on, for the next 35 years, to become an Emmy award-winning director in television, directing everything from HBO and Showtime movies to series pilots and episodic dramas. Deitch told me she thinks she was good at it but not cut out for it.

“I’m going back to my indie roots. Stay tuned.”

SCENES FROM DESERT HEARTS. PHOTOS COURTESY OF DONNA DEITCH

LEGACY OF DESERT HEARTS—SO FAR

The New Queer Cinema (a term coined by lesbian film critic B. Ruby Rich) emerged in the late 1980s and flourished in the 1990s, producing independent LGBTQ+ films that challenged conventions and norms.

Bingham Ray, an executive at the Goldwyn company, told Deitch: “You didn’t just make a film, Donna, you created a genre.”

“Donna was unbelievable,” says Charbonneau. “She worked so hard for so long for this; she even attended acting class in California for 2 years for practice. She was so ready for this, and she pulled off something that I don’t think a lot of people can pull off. She did an extraordinary thing.”

In 1996, GLAAD presented Deitch with the Woman of the Year award in recognition of Desert Hearts and her overall contributions to fair, accurate, and inclusive representation of LGBTQ+ people.

Shaver recalls the event in Beverly Hills where “all these fabulous women rose to their feet in a standing ovation, like a big wave of energy, an incredible outpouring, and I stood there thinking, Wow, I have been part of something that represents truth and beauty, and if my work never does anything else, I’ve done one thing.”

Desert Hearts has not been out of distribution in 40 years, says Deitch. First, there was the bidding war for the initial 20-year lease; then it was distributed by MGM, then Wolfe Video, and now Criterion, which restored it to 4K under Robert Elswit’s supervision. Desert Hearts returned to Sundance with the restoration in 2019, and last year it screened at the Brooklyn Academy of Music for NewFest, the 37th annual New York LGBTQ+ Film Festival, as part of its retrospective programming celebrating queer cinema.

The screening was sold out.

“There was a whole new generation seeing it for the first time,” Charbonneau tells me, revealing that she has done many events like this over the years. “The response was so new and fresh, and then afterwards I had women come up to me, and they said, Oh my God, I had heard about this film. I had no idea. I’m so glad I saw this.”

Watch Desert Hearts

In January, Curve Film Club honored Deitch with an online Criterion screening and a Q&A with special guest and super-fan Jane Lynch. Watch the recording on our YouTube channel.

Watch the 4K restoration of Desert Hearts on the Criterion Channel and see all the extras.

Tell Your Desert Hearts Story

Desert Hearts gave us permission to tell lesbian stories. What’s yours? Where were you when you first saw the movie? How did it affect your life? Donna Deitch is very interested in hearing people’s Desert Hearts coming-out stories and recording them for posterity and the collective lesbian culture.

Fill out the form, submit a link (Vimeo or YouTube) to your Video (under 2 minutes), and share your story!