Photojournalist Laila Annmarie Stevens brings attention to Audre Lorde’s overlooked life on St. Croix, continuing the legacy she established there as Gamba Adisa, Warrior.

There is a woman, her shoulders straightened back, her chin held high, leading in the direction of her hair—braids pulled into a tight ponytail. Her gaze is resonant, lacks the solidity of distinguishable eyes, pupils, or retinas, rather an ounce of white in the sea of her Black skin outlining a 1960s mod box silhouette dress. Her right hand is brazenly upwards, almost as if she were sourcing her powers unencumbered through her palms, lightly surfacing the palm tree above, below, hand, the sky meets the water waves—she stands as a divider between this environment and the metropolitan life that surrounds her. Holding both worlds within her and breathing outside of them as well.

A NEW SPELLING OF MY NAME, JUDITH’S FANCY, ST. CRIOX U.S.V.I., 2024.

PHOTO: LAILA ANNMARIE STEVENS

This is the illustrated orange cover of Audre Lorde’s 1982 Zami: A New Spelling of My Name, published by Persephone Press. By naming the text a “biomythography,” she rejected the limitations of conventional autobiography forms that had historically failed to hold Black lesbian life. In its place, she proposed a structure expansive enough to account for desire, connection, and relationships—the erotic as a source of knowledge.

Lorde’s writing affirmed that self-definition is not indulgent; it is necessary. Her insistence that Black women must name themselves—or risk being misnamed by history—has shaped generations of queer, particularly lesbian writers, artists, and organizers. The book continues to circulate through personal recommendations: passed between lovers, shared among chosen family (how I’ve gained access to this copy in my hands), and discovered through socially engaged educators and professors who push literature by Black and queer artists in classrooms, at a specific point in history when banned books are on the rise.

AUDRE LORDE. PHOTO: ARCHIVE

Born in New York City to immigrant parents from the Caribbean, Lorde’s heritage—particularly her connection to Grenada—profoundly shaped her political consciousness, language, and sense of belonging. While her writing is often situated within U.S. Black feminist and lesbian literary traditions, it is equally informed by Caribbean histories of migration, colonialism, and survival—histories that further complicate pre-established ideas of home and identity.

During the final chapter of her life, Audre Lorde made her home in St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands, where she lived openly as a lesbian alongside her partner, writer and activist Gloria Joseph. Settling on the island in the early 1980s, Lorde spent several years there before her death in 1992 at her residence in the Judith’s Fancy area. This period—marked by both deep political reflection and environmental upheaval—was shaped in part by her experience surviving Hurricane Hugo in 1989, an event that intensified her relationship to the natural world, land, ecology, and resilience in her writing and thinking.

THE DEEPEST WATER BEARER, FREDERIKSTED, U.S.V.I./ ST. CROIX, 2024.

PHOTO: LAILA ANNMARIE STEVENS

Caribbean cultures often hold queerness in tension—present but unnamed, lived but rarely archived, heard through word of mouth—spoken tales and story shares. St. Croix occupies a similarly complex position within the Caribbean and the United States: territorially American, culturally Caribbean, and frequently excluded from dominant narratives of both. For queer women on the island and in its diaspora, this dual marginalization shapes how community is built—often without outsiders’ careful eyes, more so sustained through deep interpersonal bonds and through the love of movement workers, community engaged artists, pedological thinkers, doulas and the abundance of everything in-between and above who walk in alignment with what calls them forward alongside islanders including the practices of Alexis Pauline Gumbs, djassi daCosta johnson, Mattice Haynes and many more.

Audre Lorde’s life and work speak directly across these geographies. “There is a large and ever-present Blackfullness to the days here that is very refreshing for me,” she writes in Above the Wind, 1990.

In the months following my father’s passing from cancer in 2024, I turned to archival research on Audre Lorde’s life as a way of engaging memory and confronting the emotional and political realities faced by families affected by cancer. Writing on Grenada, Alexis Pauline Gumbs notes in Survival Is a Promise: The Eternal Life of Audre Lorde that “nearly twenty years after her father’s death from extremely high blood pressure, Audre ‘ran away to be alone’ in the birthplace of her father’s silence” (237). Lorde, herself a daughter of Oya—the orisha of wind, who breathes life and the final exhalation.

BIKING, CHRISTIANSTED, ST. CROIX, U.S.V.I., 2024.

PHOTO: LAILA ANNMARIE STEVENS

During research appointments at Spelman College, an HBCU in Atlanta, Georgia, I meditated on photographs of Audre Lorde to better understand a life shaped by movement—flight, return, and acts of self-determined transformation. At the same time, Harriet Tubman’s use of the North Star—both as a literal navigational tool and a metaphoric compass—began to influence my developing visual language. Together, these histories informed Spirit Maps, an interdisciplinary project completed during my November 2025 residency at Yaddo in Saratoga Springs, New York, that examines how geography, memory, and ancestral intuition intersect.

Tubman’s life, as presented in Tiya Miles’s Night Flyer: Harriet Tubman and the Faith Dreams of a Free People, situates Tubman as a thinker, dreamer, and doer in this “faith biography,” emphasizing her spirituality and ecological awareness. Placing written accounts of Harriet Tubman in dialogue with photographic images of Audre Lorde reveals a shared framework of guidance, direction, and return. Their lives demonstrate how personal grief can intersect with cultural histories—and the archival image and spoken word can preserve the spiritual intelligence embedded within those crossings.

What if everyone knew her name? Melted in her footsteps along the shoreline? Cried themselves to sleep at night in fury and grievance? Vanished before sunlight seeped into their eyes, before trees could offer shade? Do you speak your name?

Today, as queer and trans histories face renewed efforts at erasure, Audre Lorde’s insistence on self-determination feels especially urgent. Her work reminds us that documentation—telling our own stories, on our own terms—is not merely an artistic or academic exercise, but an act of survival.

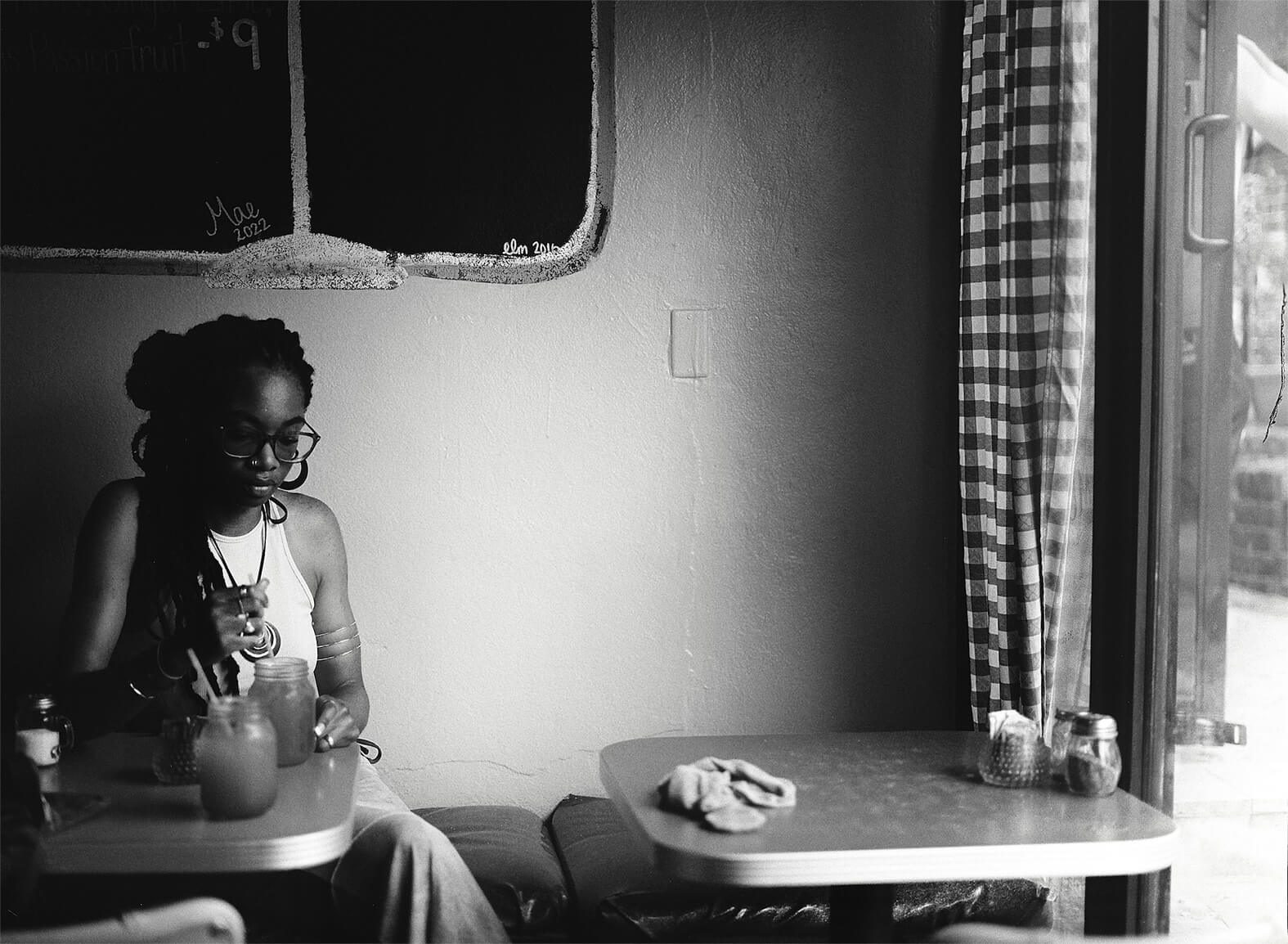

MORGAN AT CRUZIAN BAYOU BISTRO, CHRISTIANSTED, ST. CROIX, U.S.V.I., 2024.

PHOTO: LAILA ANNMARIE STEVENS

Is/As Picture Frame

For Caribbean lesbians and queer women connected to St. Croix, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and Grenada, Audre Lorde’s work carries particular resonance—offering language for lives often rendered invisible, and a framework for self-definition that continues to unfold.

I come to this work as a photojournalist and museum educator based in New York City, whose practice centers Black queer life, memory, self-determination, and how Black queer communities inherit, reinterpret, and extend cultural legacies across generations. The featured photo project ‘ZAMI’ marked a beginning—not an endpoint—in my ongoing engagement with how Black lesbians claim authorship over their own narratives.

Audre Lorde taught us that naming ourselves is a political act—and that silence, however protective it may seem, will not save us. For Caribbean queer women, Zami remains a living framework: not a fixed identity, but an ongoing process of self-definition.

The spelling is not finished. The story is still being written.

AN INVITATION TO PARTICIPATE

This piece also serves as an open call.

I am currently extending the documentary project – ZAMI, examining the impact of Audre Lorde’s life and work— on Caribbean lesbians and queer women with direct or ancestral ties to the U.S. Virgin Islands, St. John, St. Croix, St. Thomas, and Grenada, including those living in New York City or moving between both places.

I am seeking to connect with:

- Lesbians and queer women whose understanding of sexuality, identity, language, or belonging shifted after encountering Audre Lorde’s work

- Artists, writers, organizers, elders, and community members

- Those who stayed on St. Croix, those who migrated, and those navigating both worlds

Participation may include interviews, portraiture, and/or recorded conversations, depending on interest and comfort. This project is grounded in care, consent, and collaboration.

Submission Information

Interested in participating in this documentary project? Apply by completing the submission form.

All submissions will be reviewed on a rolling basis. Selected participants will be contacted directly with more information.

SELF-PORTRAIT, CHRISTANSTED, ST. CROIX, U.S.V.I., 2024.

PHOTO: LAILA ANNMARIE STEVENS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Starting with the New York Times Metropolitan section at just 20 years old, Laila Annmarie Stevens has since become a frequent contributor, first covering a Brooklyn protest titled “State of Emergency” for Trans Youth, and receiving an A1 twice before the age of 25. Her editorial work has since appeared in The Guardian US, The Nation, The Gothamist, Cultured Magazine, and other world-renowned platforms. She is the 2025 PhotoVogue Emerging Voices Grants Recipient for the “Women by Women” Open Call, 2025 NYSCA Support for Artists Grantee, 2025–2026 Curve Foundation Fellow for Emerging Journalists, Fall 2025 Artist-in-Residence at the esteemed Yaddo in Saratoga Springs, a 2023–2024 Magnum Foundation NYC Fellow, and a graduate of the Eddie Adams Workshop Class of XXXIV.

Her photographs have received a full spread in the 2025 release of Reflections in Black: A Reframing, the 25th-anniversary edition of Dr. Deborah Willis’ internationally acclaimed publication, Reflections in Black: A History of Black Photographers 1840 to the Present. Stevens has exhibited in the U.S. and internationally, including the East London Photographic Gallery (London, England), The Chrysler Museum of Art (Norfolk, Virginia), Goodyear Arts (Charlotte, North Carolina), NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts and The Center for Black Visual Culture (New York, NY) and most notably the Museum of the City of New York’s inaugural Photography Triennial, New York Now: Home (2023).

Stevens’ Guardian US assignment documenting “Black People Will Swim” (BPWS) at York College in Jamaica, Queens, was honored as one of The Guardian US’s Best Photos of 2024. She has presented artist talks and lectures at The Center for Book Arts, The Fashion Institute of Technology, and Photoville’s Educator Lab.

Penguin Classics is releasing a new deluxe hardcover Penguin vitae edition of Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (Penguin Classics, on sale February 3).

Watch Laila Annmarie Stevens’ short film ZAMI below: