In this Q&A, Executive Director Jasmine Sudarkasa interviews the Friends of the Lyon-Martin House, the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and the GLBT Historical Society on their recent collaboration with CyArk to preserve the home of Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin

Jasmine

Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin seem to be both highly visible and invisible – known to many within the lesbian community, with burgeoning awareness of their work in the broader LGBTQ+ community, but often overlooked in broader women’s history. Why do you think this is, and how have you seen this play out in the preservation of their home?

Grete Miller,

Co-Director, Friends of the Lyon-Martin House

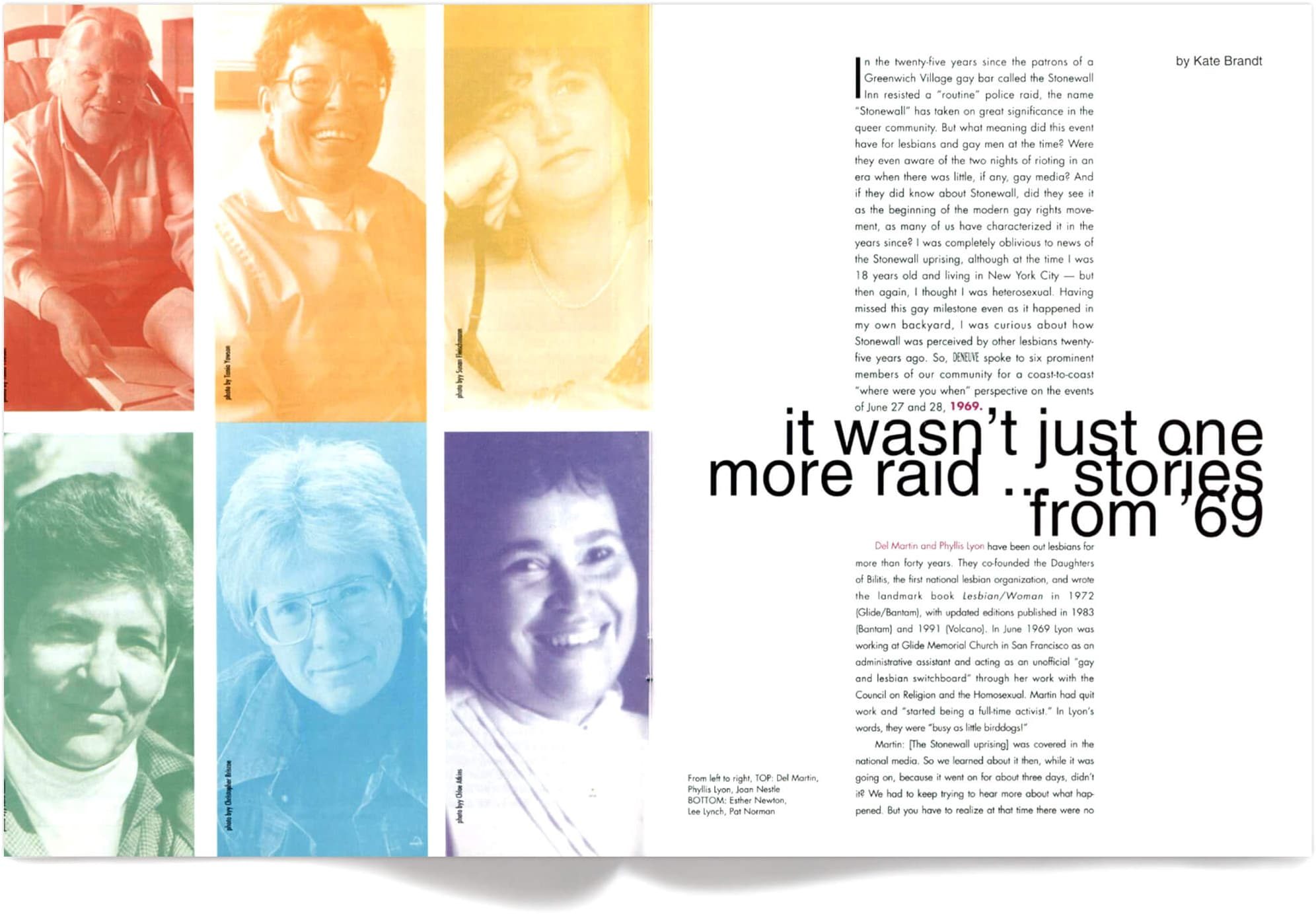

I think when you’re looking at the lives of long-term intersectional activists, such as Phyllis & Del, you realize how broad their service vision was. They were involved in an extensive range of social justice initiatives. They don’t fit into a single issue box. For as much as they’re remembered, they’re also not as visible to people outside of certain communities and generational circles.

That said, when we think about the queer stories and histories that get circulated by mainstream media, the breath of material is concentrated around Stonewall and after. The Homophile organizations that laid the groundwork for the modern-day LGBTQ+ rights movement are typically left out. Sadly, this furthers the erasure of lesbians and queer women who championed the early movement.

As a community, we haven’t been able to document our history and receive the resourcing to preserve our contributions in parity with societal majorities. When you’re not permitted to archive and preserve your history in an inclusive, equitable and accurate way, it’s very difficult to capture and reclaim your story. It hasn’t helped that our stories and representation have often been associated with shame, stigma, and falsehoods, and have been catalogued under damaging and harmful terminology. There’s ongoing work to change this but we still have a long way to go.

We also have to acknowledge that it was much harder for people to be “out” in the early movement. Great lengths were taken to protect identities. Fake names and coded phrasing were used in communications. People destroyed their own materials to protect themselves. Families discarded the belongings of deceased gay relatives to hide their homosexuality. These factors make it difficult to prove the historic worth of LGBTQ+ people and places. When held up against the narrow processes and heteronormative criteria implemented by formal institutions, justice, diversity, equity, and inclusion (JDEI) are not given their due recognition – leaving people’s stories, places and contributions behind.

You can’t fault people, especially LGBTQ+ youth for not knowing their history. After all, you don’t know what you don’t know and you don’t know what you’re not being taught. We’re living in a time when only five U.S states have public school curricula that legally require LGBTQ+ history lessons in history classes, while other states have policies in place that don’t permit queer-inclusive and accessible education.

There are many barriers to accessing LGBTQ+ history, especially that of our lesbian foremothers. In the case of Lyon-Martin House, it was a humble structure that didn’t present many character defining features warranting preservation. Therefore, Friends of Lyon-Martin House and our partners at the GLBT Historical Society, San Francisco Heritage and the National Trust for Historic Preservation built a case to validate that the pioneering work conducted within the home was worth preserving. Thus, saving the house. Like Phyllis & Del, all we needed was a challenge and we succeeded.

Inside the walls of 651 Duncan, history was made and new leaders were born into the LGBTQ+ rights movement. Phyllis and Del organized activists to validate and decriminalize my life and the lives of many others. From inside their house, they forced the world to change and turn toward the side of justice. There is power in knowing your history and being able to touch your story. The strength of your elders teaches you what is possible, and that your life has purpose. I know that because they did, I can.

Andrew Shaffer,

Interim Co-Executive Director, GLBT Historical Society

Grete is exactly right, there are so few opportunities for people to learn about LGBTQ history. So much of our history has been erased, which is why this kind of work is so crucial. It really is up to us to tell our stories because no one will do it for us.

The Society holds an enormous archive of material from Phyllis and Del. It’s one of our largest, as well as being among our most requested collections. So, when the call came to help preserve the house, we immediately stepped up to sponsor the project and established a preservation fund, which is currently accepting donations. For us, this is an obvious extension of our ongoing work to keep these stories alive.

Jasmine

Why preserve their home digitally? Who does this work reach that it might not, otherwise?

Grete Miller

To mitigate the risk of losing visual data and storytelling elements, I thought it was important that we collect the visual story of the house, create an accessible digital experience for the community, and preserve that raw data for future generations. Not only that, the work is critical to provide much broader public access to the physical property. The house is a small 800 sf property in a residential neighborhood and would have extremely limited physical access even in the best circumstances. Providing a user-friendly digital experience offers an opportunity to reach a national and global audience with the story of Lyon and Martin’s decades of activism for LGBTQ+ and civil rights.

Some people have asked why the digital documentation matters and why we’re doing this. My question is, what happens if we don’t? What do we risk losing by not collecting this information and creating this platform for our communities? We’re living through a global pandemic, climate change and around the world we’re witnessing growing hostilities towards LGBTQ+ people. The right time to do this is now. We have the tools and technology – let’s do it.

Documenting the spaces of historically excluded people is vital for individuals whose stories have been forgotten or purposely neglected. If we can preserve not only the physical site but the full visual story and experience of iconic places like the Lyon-Martin House, decades later we will have a valuable collection of content to look back on. Each still, moving image, and 3D scan will make visible what was invisible, and preserve the source of a movement and make it accessible to others. In doing so, these mediums push back against erasure and celebrate diverse communities and people whose stories haven’t been told. It allows us to be a part of another person’s truth and grow through their incomparable contributions and legacy.

Andrew Shaffer

The Society has been actively preserving stories like these for more than three decades, keeping them safe in our archives for current and future generations who want to learn their history. One thing that we learned clearly from the last year is that we need to make more of our resources available online. Not only in case of a pandemic, but also for the countless people all over the world who are searching for their place in history. They have a right to know their history, and we have an obligation to help them find it.

In addition to our new primary source set about Phyllis and Del’s lives, the digital documentation of their home adds a crucial dimension to our efforts to preserve the legacy of this pioneering couple. Being able to virtually walk through the home where so much history happened is going to make the rest of the materials in our collection that much more powerful.

Chris Morris,

Campaign for Where Women Made History, National Trust for Historic Preservation

The protection, elevation, and restoration of the Lyon-Martin House is part of the National Trust’s commitment to tell a more full and accurate American story. Our campaign for Where Women Made History is dedicated to lifting up the stories and places of women’s achievement where they have changed their communities and changed the world. We seek to bring them the national visibility and the respect that they deserve and in doing so, inspire a new generation of young women and men who are still writing their own stories.

One of the joys of this project is how it has attracted so many different organizations and partners in such a short amount of time. All of us immediately grasped the significance of Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin’s activism, the positive impact their actions had on millions of people’s lives, and how relevant their work is today amid constant challenges to the rights of women, the LGBTQ community, and people of color.

At a time when there was so much fear and discrimination and so much to lose, when your choices in partner often resulted in institutionalization, incarceration, or worse, Phyllis and Del made the difficult decision not keep the Daughters of Bilitis a secret social club, but instead pushed for social change through recognition, public education, and understanding. It’s an instructive and inspiring example for anyone who continues to advocate for gender equality, marriage equality, social justice, and the protection of civil rights.

Jasmine

I’d love to know more about the process of scanning/cataloguing the home, and innovations in making preservation work live in the digital space.

Grete Miller

Digital documentation is critical for physical places and spaces. It’s not a replacement for the physical, in-person experience. However it provides a different level of access and information that enhances understanding and personal connection to the place and the people and events associated with it. It allows people to explore at their own pace, and pursue the avenues and issues that interest them the most.

We regularly asked ourselves, “Who are we serving?” and “What problems are we working to solve?” From an inclusive product perspective, it wasn’t just about the basic tech set-up but making a commitment to build JDEI into the experience. We moved beyond academia and focused on mapping out a narrative for the general public, specifically LGBTQ+ youth. Our goal was to create an experience that felt approachable, removed accessibility and privilege-based barriers, provided digestible information, emotionally connected with our viewers and left them feeling empowered to engage with their community for positive change.

Today archival spaces still present various challenges to the general public, especially for marginalized communities. The complex navigational blockers and processes that exist prevent people from locating the content they need, validating their lived experience, and seeing their story told with dignity.

In order to know your audience’s needs, you must consult and collaborate with diverse subject matters and community leaders on defining your requirements. If not, future archives, historical and preservation platforms will not grow and flourish as inclusive intersectional environments that welcome all users and validate their belonging. Instead they will continue to be a convoluted experience, clouded in the stereotypes and reinforcing to users that, “this isn’t for you.’”

Chris Morris

What’s exciting to me about the digital documentation project with CyArk is that it’s as much about shaping the future of the Lyon-Martin House as it is about preserving its past. We don’t want to freeze the physical building and site at a specific moment in time. We understand this place as a repository for multiple historic events that spanned five decades of Phyllis and Del’s life and work. And while it’s critical that we document and preserve that history for posterity, we also need to consider how those historical events can inform and shape our future. The digital documentation provides a framework that we can use to communicate with the public; collaborate with members of the LGBTQ community, multiple stakeholders and partners; assess the property’s condition and potential; and explore a range of options for restoring and reviving the Lyon-Martin House as new home of LGBTQ activism, learning, and leadership. It’s equally important that we consider how to honor Phyllis and Del’s legacy and how to carry it forward.

Jasmine

Lastly – what are the next steps for this project? What are your broader hopes for its visibility?

Chris Morris

There has been remarkably rapid progress in just the last few months, with the San Francisco Landmark designation, led by the Friends of Lyon-Martin House, Supervisor Rafael Mandelman, and the GLBT Historical Society, the local and national coverage of that designation bringing attention to the property and its importance, and the partnership with CyArk to do highly detailed digital scans, site photography, and a short documentary. But we are only at the beginning of what is likely to be a long journey since our goal is not merely to protect the house, but to restore and reactivate it as a site for LGBTQ research, advocacy, or activism.

One of the first goals is outreach to the LBGTQ community to hear their ideas and aspirations for the Lyon-Martin House, and their suggestions for potential partner organizations, all of which will inform a plan for the future of the house. Just a few of the ideas that have been suggested so far are an “activist-in-residence” working on LGBTQ policies and issues, a dedicated researcher for the GLBT Historical Society to catalog and interpret the Lyon Martin archives, or affordable, safe housing in partnership with an organization that serves LGBTQ and women victims of violence. Over the next few months, we’ll need to work with design professionals to conduct a preliminary assessment of the building and grounds. This will help us determine what types of stabilization and immediate repairs are needed to make the building safe and accessible, and give us estimates for the costs of those repairs.

Over the long term we want to pursue designation of the property as a National Historic Landmark. While this is a time-consuming and costly process, it’s important as a declaration of the national significance of the Lyon-Martin House and its history. Conceptual designs will create a visual representation of the future uses, which we can present to partners, supporters, and funders. Ultimately, we hope it’s possible to acquire the property outright or enter into a long-term lease with the current owner, allowing non-profit organizations to use the house and grounds. But all of these items require time and resources. We need visibility, public support, and funding to make all this work possible.

For anyone who is moved by the achievements of Phyllis Lyon and Del Martin—two towering figures of LGBTQ civil rights and women’s rights movements–and interested in assisting us with the preservation and reactivation of the Lyon-Martin House, we urge you to join our efforts and make a donation today (url for donations https://www.glbthistory.org/lyon-martin-house)